Title: Lives of the Most Remarkable Criminals Who have been Condemned and Executed for Murder, the Highway, Housebreaking, Street Robberies, Coining or other offences

Editor: Arthur Lawrence Hayward

Release date: August 3, 2004 [eBook #13097]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Eloise Mason and Cally Soukup, and PG Distributed

Proofreaders

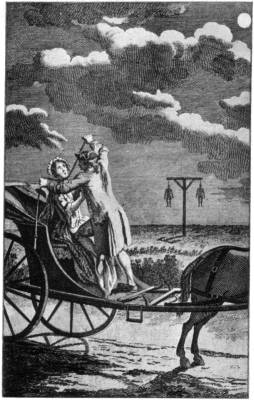

The assailant is strangling his victim with a whip-thong; nearby is a

typical roadside gallows with two highwaymen dangling from the

cross-tree

(From the Newgate Calendar)

Preface—Jane Griffin—John Trippuck, Richard Cane and Richard Shepherd—William Barton—Robert Perkins—Barbara Spencer—Walter Kennedy—Matthew Clark—John Winship—John Meff—John Wigley—William Casey—John Dykes—Richard James—James Wright—Nathaniel Hawes—John Jones—John Smith—James Shaw, alias Smith—William Colthouse—William Burridge— John Thomson—Thomas Reeves—Richard Whittingham—James Booty—Thomas Butlock—Nathaniel Jackson—James Carrick—John Molony—Thomas Wilson—Robert Wilkinson and James Lincoln—Mathias Brinsden—Edmund Neal—Charles Weaver—John Levee—Richard Oakey and Matthew Flood—William Burk—Luke Nunney—Richard Trantham—John Tyrrell and William Hawksworth—William Duce—James Butler—Captain John Massey—Philip Roche—Humphrey Angier—Captain Stanley—Stephen Gardiner—Samuel Ogden, John Pugh, William Frost, Richard Woodman and William Elisha—Thomas Burden—Frederick Schmidt—Peter Curtis—Lumley Davis—James Harman—John Lewis— The Waltham Blacks—Julian, a Black Boy—Abraham Deval—Joseph Blake, alias Blueskin—John Shepherd—Lewis Houssart—Charles Towers—Thomas Anderson—Joseph Picken—Thomas Packer—Thomas Bradely—William Lipsat—John Hewlet—James Cammell and William Marshal—John Guy—Vincent Davis—Mary Hanson—Bryan Smith—Joseph Ward—James White—Joseph Middleton—John Price

Preface—William Sperry—Robert Harpham—Jonathan Wild—John Little—John Price—Foster Snow—John Whalebone—James Little—John Hamp—John Austin, John Foster and Richard Scurrier—Francis Bailey—John Barton—William Swift—Edward Burnworth, etc.—John Gillingham—John Cotterel—Catherine Hayes—Thomas Billings—Thomas Wood—Captain Jaen—William Bourn—John Murrel—William Hollis—Thomas Smith—Edward Reynolds—John Claxton—Mary Standford—John Cartwright—Frances Blacket—Jane Holmes—Katherine Fitzpatrick—Mary Robinson—Jane Martin—Timothy Benson—Joseph Shrewsberry—Anthony Drury—William Miller—Robert Haynes—Thomas Timms, Thomas Perry and Edward Brown—Alice Green—An Account of the Murder of Mr. Widdington Darby—Joshua Cornwall

John Turner, alias Civil John—John Johnson—James Sherwood, George Weldon and John Hughs—Martin Bellamy—William Russell, Robert Crough and William Holden—Christopher Rawlins, etc.—Richard Hughes and Bryan MacGuire—James How—Griffith Owen, Samuel Harris and Thomas Medline—Peter Levee, etc.—Thomas Neeves—Henry Gahogan and Robert Blake—Peter Kelley—William Marple and Timothy Cotton—John Upton—Jephthah Bigg—Thomas James Grundy—Joseph Kemp—Benjamin Wileman—James Cluff—John Dyer—William Rogers, William Simpson and Robert Oliver—James Drummond—William Caustin and Geoffrey Younger—Henry Knowland and Thomas Westwood—John Everett—Robert Drummond and Ferdinando Shrimpton—William Newcomb—Stephen Dowdale—Abraham Israel—Ebenezer Ellison—James Dalton—Hugh Houghton—John Doyle—John Young—Thomas Polson—Samuel Armstrong—Nicholas Gilburn—James O'Bryan, Hugh Morris and Robert Johnson—Captain John Gow

John Perry—William Barwick—Mr. Walker and Mark Sharp—Jacques Perrier—Abraham White, Francis Sanders, John Mines alias Minsham, alias Mitchell, and Constance Buckle

| Murder on Hounslow Heath | Frontispiece |

| Matthew Clark cutting the throat of Sarah Goldington | 40 |

| A Prisoner Under Pressure in Newgate | 63 |

| The Hangman arrested when attending John Meff to Tyburn | 113 |

| Stephen Gardiner making his dying speech at Tyburn | 147 |

| Jack Sheppard in the Stone Room in Newgate | 187 |

| Trial of a Highwayman at the Old Bailey | 225 |

| Jonathan Wild pelted by the mob on his way to Tyburn | 272 |

| A Condemned Man drawn on a Sledge to Tyburn | 305 |

| The Murder of John Hayes: | |

| Catherine Hayes, Wood and Billings cutting off the head | 336 |

| John Hayes's Head exhibited at St. Margaret's, Westminster | 346 |

| Catherine Hayes burnt for the murder of her husband | 353 |

| Joseph Blake attempting the life of Jonathan Wild | 416 |

| An Execution in Smithfield Market | 465 |

| Highway Robbery of His Majesty's Mail | 538 |

| A Gang of Men and Women Transports being marched from Newgate to Blackfriars | 593 |

If there be a haunted spot in London it must surely be a few square yards that lie a little west of the Marble Arch, for in the long course of some six centuries over fifty thousand felons, traitors and martyrs took there a last farewell of a world they were too bad or too good to live in. From remote antiquity, when the seditious were taken ad furcas Tyburnam, until that November day in 1783 when John Austin closed the long list, the gallows were kept ever busy, and during the first half of the eighteenth century, with which this book deals, every Newgate sessions sent thither its thieves, highwaymen and coiners by the score.

There has been some discussion as to the exact site of Tyburn gallows, but there can be little doubt that the great permanent three-beamed erection—the Triple Tree—stood where now the Edgware Road joins Oxford Street and Bayswater Road. A triangular stone let into the roadway indicates the site of one of its uprights. In 1759 the sinister beams were pulled down, a moveable gibbet being brought in a cart when there was occasion to use it. The moveable gallows was in use until 1783, when the place of execution was transferred to Newgate; the beams of the old structure being sawn up and converted to a more genial use as stands for beer-butts in a neighbouring public-house.

The original gallows probably consisted of two uprights with a cross-piece, but when Elizabeth's government felt that more adequate means must be provided to strengthen its subjects' faith and enforce the penal laws against Catholics, a new type of gibbet was sought. So in 1571 the triangular one was erected, with accommodation for eight such miscreants on each beam, or a grand total of twenty-four at a stringing. It was first used for the learned Dr. John Story, who, upon June 1st, "was drawn upon a hurdle from the Tower of London unto Tyburn, where was prepared for him a new pair of gallows made in triangular manner". There is rather a gruesome tale of how, when in pursuance of the sentence the executioner had cut him down and was "rifling among his bowels", the doctor arose and dealt him a shrewd blow on the head. Doctor Story was followed by a long line of priests, monks, laymen and others who died for their faith to the number of some three thousand. And the Triple Tree, the Three-Legged Mare, or Deadly Never-green, as the gallows were called with grim familiarity, flourished for another two hundred years.

In the early eighteenth century it appears to have been the usual custom to reserving sentencing until the end of the sessions, but as soon as the jury's verdict of guilty was known steps were taken to procure a pardon by the condemned man's friends. They had, indeed, much more likelihood of success in those times when the Law was so severe than in later days when capital punishment was reserved for the most heinous crimes. On several occasions in the following pages mention is made of felons urging their friends to bribe or make interest in the right quarters for obtaining a pardon, or commutation of the sentence to one of transportation. It was not until the arrival of the death warrant that the condemned man felt that the "Tyburn tippet" was really being drawn about his neck.

No better description can be given of the ride to Tyburn tree, from Newgate and along Holborn, than that furnished by one of the Familiar Letters written by Samuel Richardson in 1741:

I mounted my horse and accompanied the melancholy cavalcade from Newgate to the fatal Tree. The criminals were five in number. I was much disappointed at the unconcern and carelessness that appeared in the faces of three of the unhappy wretches; the countenance of the other two were spread with that horror and despair which is not to be wondered at in men whose period of life is so near, with the terrible aggravation of its being hastened by their own voluntary indiscretion and misdeeds. The exhortation spoken by the Bell-man, from the wall of St. Sepulchre's churchyard is well intended; but the noise of the officers and the mob was so great, and the silly curiosity of people climbing into the cart to take leave of the criminals made such a confused noise that I could not hear the words of the exhortation when spoken, though they are as follows:

All the way up to Holborn the crowd was so great as at every twenty or thirty yards to obstruct the passage; and wine, notwithstanding a late good order against this practice, was brought to the malefactors, who drank greedily of it, which I thought did not suit well with their deplorable circumstances. After this the three thoughtless young men, who at first seemed not enough concerned, grew most shamefully wanton and daring, behaving, themselves in a manner that would have been ridiculous in men in any circumstances whatever. They swore, laughed, and talked obscenely, and wished their wicked companions good luck with as much assurance as if their employment had been the most lawful.

At the place of execution the scene grew still more shocking, and the clergyman who attended was more the subject of ridicule than of their serious attention. The Psalm was sung amidst the curses and quarrelling of hundreds of the most abandoned and profligate of mankind, upon them (so stupid are they to any sense of decency) all the preparation of the unhappy wretches seems to serve only for subject of a barbarous kind of mirth, altogether inconsistent with humanity. And as soon as the poor creatures were half dead, I was much surprised to see the populace fall to hauling and pulling the carcasses with so much earnestness as to occasion several warm rencounters and broken heads. These, I was told, were the friends of the persons executed, or such as, for the sake of to-night, chose to appear so: as well as some persons sent by private surgeons to obtain bodies for dissection. The contests between these were fierce and bloody, and frightful to look at; so I made the best of my way out of the crowd, and with some difficulty rode back among the large number of people who had been upon the same errand as myself. The face of every one spoke a kind of mirth, as if the spectacle they had beheld had afforded pleasure instead of pain, which I am wholly unable to account for....

One of the bodies was carried to the lodging of his wife, who not being in the way to receive it, they immediately hawked it about to every surgeon they could think of; and when none would buy it they rubbed tar all over it, and left it in a field scarcely covered with earth.

In a few words, too, Swift draws a vivid picture of a rogue on his last journey through the London streets:

Execution day, or Tyburn Fair, as it was jocularly called, was not only a holiday for the ragamuffins and idlers of London; folk of all classes made their way thither to indulge a morbid desire of seeing the dying agonies of a fellow being, criminal or not. There were grand stands and scaffoldings from which the more favoured could view the proceedings in comfort, and every inch of window space and room on the neighbouring roofs was worth a pretty penny to the owners. In his last scene of the career of the Idle Apprentice Hogarth drew a picture of Tyburn Tree which no description can amplify.

As the procession drew near the hangman clambered to the cross-piece of the gallows and lolled there, pipe in mouth, until the first cart drew up beneath him. Then he would reach down, or one of his assistants would pass up, one after the other, the loose ends of the halters which the condemned men had had placed round their necks before leaving Newgate. When all were made fast Jack Ketch climbed down and kicked his heels until the sheriff, or maybe the felons themselves, gave him the sign to drive away the cart and leave its occupants dangling in mid-air. The dead men's clothes were his perquisite, and now was his time to claim them. There is a graphic description of how, on one occasion, when the murderer "flung down his handkerchief for the signal for the cart to move on, Jack Ketch, instead of instantly whipping on the horse, jumped on the other side of him to snatch up the handkerchief, lest he should lose his rights. He then returned to the head of the cart and jehu'd him out of the world".

As the cart drew away a few carrier pigeons, which were released from the galleries, flew off City-ward to bear the tidings to Newgate.

Perhaps as good a description of the actual event as can be obtained is contained in a letter from Anthony Storer to his friend George Selwyn, a morbid cynic whose cruel and tasteless bon-mots were hailed as wit by Horace Walpole and his cronies. The execution was that of Dr. Dodd, the "macaroni parson", whose unfortunate vanity led him to forgery and Tyburn. The date—June 27, 1777—is considerably after the period of our book, but the description applies as well as if it had been written expressly for it.

Upon the whole, the piece was not very full of events. The doctor, to all appearances, was rendered perfectly stupid from despair. His hat was flapped all round, and pulled over his eyes, which were never directed to any object around, nor even raised, except now and then lifted up in the course of his prayers. He came in a coach, and a very heavy shower of rain fell just upon his entering the executioner's cart, and another just at his putting on his nightcap. During the shower an umbrella was held over his head, which Gilly Williams, who was present, observed was quite unnecessary, as the doctor was going to a place where he might be dried.

He was a considerable time in praying, which some people standing about seemed rather tired with; they rather wished for a more interesting part of the tragedy. The wind, which was high, blew off his hat, which rather embarrassed him, and discovered to us his countenance, which we could scarcely see before. His hat, however, was soon restored to him, and he went on with his prayers. There were two clergymen attending on him, one of whom seemed very much affected. The other, I suppose, was the Ordinary of Newgate, as he was perfectly indifferent and unfeeling in everything he did and said.

The executioner took both the hat and wig off at the same time. Why he put on his wig again I do not know, but he did; and the doctor took off his wig a second time, and then tied on the nightcap which did not fit him; but whether he stretched that or took another, I did not perceive. He then put on his nightcap himself, and upon his taking it he certainly had a smile on his countenance, and very soon afterwards there was an end of all his hopes and fears on this side of the grave. He never moved from the place he first took in the cart; seemed absorbed in despair and utterly dejected; without any other sign of animation but in praying. I stayed until he was cut down and put in the hearse.

But the hangman's work was not always done when he had turned off his man. The full sentence for high treason, for example, provided him with much more occupation. In the first place, the criminal was drawn to the gallows and not carried or allowed to walk. Common humanity had mitigated this sentence to being drawn upon a hurdle or sledge, which preserved him from the horrors of being dragged over the stones. Having been hanged, the traitor was then cut down alive, and Jack Ketch set about disembowelling him and burning his entrails before he died. The head was then completely severed, the body quartered and the dismembered pieces taken away for exhibition at Temple Bar and other prominent places.

Here is the account of one such execution. "After the traitor had hung six minutes he was cut down, and having life in him, as he lay upon the block to be quartered, the executioner gave him several blows on his breast, which not having the effect designed, he immediately cut his throat; after which he took his head off; then ripped him open and took out his bowels and heart, and then threw them into a fire which consumed them. Then he slashed his four quarters and put them with the head into a coffin.... His head was put on Temple Bar and his body and limbs suffered to be buried."

Such proceedings were exceptional, however. In the majority of executions the body was taken down when life was considered to be extinct, and carried away to Surgeon's Hall for dissection. Sometimes the relatives used their influence to have the corpse handed over to them (often not even in a coffin) and they then carried it away in a coach for decent burial, or to try resuscitation. Occasionally, indeed, hanged men came to life again. In 1740 one Duel, or Dewell, was hanged for a rape, and his body taken to Surgeons' Hall in the ordinary routine. As one of the attendants was washing it he perceived signs of life. Steps were taken immediately and Duel was brought to, and eventually taken away in triumph by the mob, who had got wind of the affair and refused to allow the Law to re-hang their man. A little earlier something of the same sort had happened to John Smith, who had been hanging for five minutes and a quarter, during which time the hangman "pulled him by the legs and used other means to put a speedy period to his life", when a reprieve arrived and he was cut down. He was hurried away to a neighbouring tavern where restoratives were given, blood was let, and after a time he came to himself, "to the great admiration of the spectators". According to his own account of the affair, he felt a terrible pain when first the cart drew away and left him dangling, but that ceased almost at once, his last sensation being that of a light glimmering fitfully before his eyes. Yet all his previous agony was surpassed when he was being brought to, and the blood began to circulate freely again. A last ignominy, and one strangely dreaded by some of the most hardened criminals, was hanging in irons. When life was extinct the corpse was placed in a sort of iron cage and thus suspended from a gibbet, usually by the highway or near the place where the crime had been committed. There it hung until it fell to pieces from the effects of Time and the weather, and only a few hideous bones and scraps of dried flesh remained as evidence of the strong hand of the Law.

With the exception of minor alterations in punctuation and spellings this book is a complete reprint of three volumes printed and sold by John Osborn, at the Golden Ball, in Paternoster Row, 1735.

A. L. H.

The clemency of the Law of England is so great that it does not take away the life of any subject whatever, but in order to the preservation of the rest both by removing the offender from a possibility of multiplying his offences, and by the example of his punishment intending to deter others from such crimes as the welfare of society requires should be punished with the utmost severity of the Law. My intention in communicating to the public the lives of those who, for about a dozen years past have been victims to their own crimes, is to continue to posterity the good effects of such examples, and by a recital of their vices to warn those who become my readers from ever engaging in those paths which necessarily have so fatal an end. In the work itself I have, as well as I am able, painted in a proper light those vices which induce men to fall into those courses which are so justly punished by the Legislature.

I flatter myself that however contemptible the Lives of the Criminals, etc., may seem in the eyes of those who affect great wisdom and put on the appearance of much learning, yet it will not be without its uses amongst the middling sort of people, who are glad to take up with books within the circle of their own comprehension. It ought to be the care of all authors to treat their several subjects so that while they are read for the sake of amusement they may, as it were imperceptibly, convey notions both profitable and just. The adventures of those who, for the sake of supplying themselves with money for their debaucheries, have betaken themselves to the desperate trade of knights of the road, often have in them circumstances diverting enough and such as serve to show us what sort of amusements they are by which vice betrays us to ruin, and how the fatal inclination to gratify our passions hurries us finally to destruction.

I would not have my readers imagine however, because I talk of rendering books of this kind useful, that I have thrown out any part of what may be styled interesting. On the contrary, I have carefully preserved this and as far as the subject would give me leave, improved it, but with this caution always, that I have set forth the entertainments of vice in their proper colours, lest young people might be led to take them for innocent diversions, and from figures not uncommon in modern authors, learn to call lewdness gallantry, and the effects of unbridled lust the starts of too warm an imagination. These are notions which serve to cheat the mind and represent as the road of pleasure that which is indeed the highway to the gallows. This, I conceived, was the use proper to be made of the lives, or rather the deaths of malefactors, and if I have done no other good in writing them, I shall have at least this satisfaction, that I have preserved them from being presented to the world in such a dress as might render the Academy of Thieving their proper title, a thing once practised before, and if one may guess from the general practice of mankind, might probably have been attempted again, with success. How a different method will fare in the world, time only can determine, and to that I leave it. Yet considering the method in which I treat this subject, I readily forsaw one objection which occasioned my writing so long a preface as this, in order that it might be fully obviated.

Though in the body of the work itself I have carefully traced the rise of those corrupt inclinations which bring men to the committing of facts within the cognizance of the Law, it still remains necessary that my readers also become acquainted, at least in general, with what those facts are which are so severely punished. In doing this I shall not speak of matters in the style of a lawyer, but preserve the same plainness of language which, as I thought it the most proper, I have endeavoured throughout the whole piece.

The order of things requires that I should first of all take notice how the Law comes to have a right of punishing those who live under it with Death or other grievous penalties, and this in a few words arises thus. We enter into society for the sake of protection, and as this renders certain laws necessary, we are justly concluded by them in other cases for the protection of others; but of all the criminal institutions which have been settled in any nation, never was any more just, more reasonable, or fuller of clemency, than that which is called the Crown Law in England. In speaking of this it may not be improper to explain the meaning of that term, which seems to take its rise from the conclusion of indictments, which run always contra pacem dicti domini regis, coronam et dignitatem suam (against the peace of our Sovereign Lord the King, his Crown and Dignity) and therefore, as the Crown is always the prosecutor against such offenders, the Law which creates the offence is with propriety enough styled the Crown Law.

The first head of Crown Law is that which concerns offences committed against God, and anciently there were three which were capital, viz., heresy, witchcraft and sodomy; but the law passed in the reign of King Charles the Second for taking away the writ de Hæretica comburendo, leaves the first not now punishable with death, even in its highest degree. However, by a statute made in the reign of King William, persons educated in the Christian religion who are convicted of denying the Trinity, the Christian religion, or the authority of the Scriptures, are for the first offence to be adjudged incapable of office, for the second to be disabled from suing in any action, and over and above other incapacities to suffer three years' imprisonment. As to witchcraft, it was formerly punished in the same manner as heresy. In the time of Edward the Third, one taken with the head and face of a dead man and a book of sorcery about him, was brought into the King's Bench, and only sworn that he would not thenceforth be a sorcerer, and so dismissed, the head, however, being burnt at his charge. There was a law made against conjurations, enchantments and witchcraft, in the days of Queen Elizabeth, but it stands repealed by a statute of King James's time, which is the law whereon all proceedings at this day are founded. By this law, any person invoking or conjuring any evil spirit, covenanting with, employing, feeding, or rewarding them, or taking up any dead person out of their grave, or any part of them, and making use of it in any witchcraft, sorcery, etc., shall suffer death as a felon, without benefit of clergy, and this whether the spirits appear, or whether the charm take effect or no. By the same statute those who take upon them by witchcraft, etc., to tell where treasure is hid, or things lost or stolen should be found, or to engage unlawful love, shall suffer for the first offence a year's imprisonment, and stand in the pillory once every quarter in that year six hours, and if guilty a second time, shall suffer death; even though such discoveries should prove false, or charms, etc., should have no effect. Executions upon this Act were heretofore frequent, but of late years, prosecutions on these heads in which vulgar opinion often goes a great way have been much discouraged and discontinued. As for the last head it remains yet capital, by virtue of a statute made in the reign of Henry VIII, which had been repealed in the first of Queen Mary, and was revived in the fifth of Queen Elizabeth, by which statute, after reciting that the laws then in being in this realm were not sufficient for punishing that detestable vice, it is enacted that such crimes for the future, whether committed with mankind or beasts, should be punished as felonies without benefit of clergy.

It is wide of my purpose to dwell any longer on those crimes which are by the laws styled properly against God, seeing none of the persons mentioned in the following work were executed for doing anything against them. Let us therefore pass on to the second great branch of the Crown Law, viz., offences immediately against the King, and these are either treasons or felonies. Of treasons there are four kinds, all settled by the Statute of the 25th of Edward the Third. The two latter only, viz., offences against the King's great or privy seal, and offences in counterfeiting money, have anything to do with our present design, and therefore we shall speak particularly of them. Not only the persons who actually counterfeit those seals, but even the aiders and consenters to such counterfeiting, are within the Act, and by a statute made in the reign of Queen Mary, counterfeiting the sign manual or privy signet, is also made high treason. By the same statute of Edward the Third, the making of false money, or the bringing it into this realm, in deceit of our Lord the King and his people, was also declared to be high treason, but this Act being found insufficient, clippers being not made guilty either of treason or of misprison of treason, it was helped in that respect by several other Acts; but the fullest of all was the Act made in the reign of the late King William, and rendered perpetual by a subsequent Law made in the reign of her late Majesty [Anne], whereby it is enacted, that whoever shall make, mend, buy, sell, or have in his possession, any mould or press for coining, or shall convey such instruments out of the King's Mint, or mark on the edges of any coin current or counterfeit, or any round blanks of base metal, or colour or gild any coin resembling the coin of this kingdom, shall suffer death as in case of high treason. At the time when these laws were made coining and clipping were at a prodigious height, and practised not only by mean and indigent persons but also by some of tolerable character and rank, insomuch that these executions were numerous for some years after passing the said Act, which as it created some new species of high treason, so it also made felony some other offences against the coin which were not so, or at least were not clearly so before, viz., to blanch copper for sale; or to mix blanch copper with silver, or knowingly or fraudulently to buy any mixture which shall be heavier than silver, and look, touch, and wear like gold, but be manifestly worse; or receive, or pay any counterfeit money at a lower rate than its denomination doth import, shall be guilty of felony.

A third head under which, in this cursory account of Crown Law, I shall range other offences that are punished capitally, are those against our fellow subjects, and they are either committed against their lives, their goods or their habitations. With respect to those against life, if one person kill another without any malice aforethought, then that natural tenderness of which the Law of England is full, interposes for the first fact, which in such a case is denominated manslaughter. Yet there is a particular kind of manslaughter which, by the first of King James, is made felony without benefit of clergy, and that is, where a person shall stab or thrust any person or persons that have not any weapon drawn (or that have not first struck the party which shall so stab or thrust), so that the person or persons so stabbed or thrust shall die within six months next following, though it cannot be proved that the same was done of malice aforethought. This Act it is which is commonly called the Statute of Stabbing.

As to murder properly so called, and taking it as a term in the English Law, it signifies the killing of any person whatsoever from malice aforethought, whether the person slain be an Englishman or not, and this may not only be done directly by a wound or blow, but also by deliberately doing a thing which apparently endangers another's life, so that if death follow thereon he shall be adjudged to have killed him. Such was the case of him who carried his sick father from one town to another against his will in a frosty season. It would be too long for this Preface, should I endeavour to distinguish the several cases which in the eye of the Law come under this denomination; having, therefore, a view to the work itself, I shall distinguish two points only from which malice prepense is presumed in Law.

(1) Where an express purpose appears in him who kills, to do some personal injury to him who is slain; in which case malice is properly to be expressed.

(2) Where a person in the execution of an unlawful action kills another, though his principal intent was not to do any personal injury to the person slain; in which case the malice is said to be implied.

As to duels where the blood has once cooled, there is no doubt but he who kills another is guilty of wilful murder; or even in case of a sudden quarrel, if the person killing appear by any circumstance to be master of his temper at the time he slew the other, then it will be murder. Not that the English Law allows nothing to the frailties of human nature, but that it always exerts itself where there appears to have been a person killed in cool blood. Far this reason the seconds at a premeditated duel have been held guilty of murder, nor will the justice of the English Law be defeated where a person appears to have intended a less hurt than death, if that hurt arose from a desire of revenge in cool blood; for if the person dies of the injury it will be murder. So, also, where the revenge of a sudden provocation is executed in a cruel manner, though without intention of death, yet if it happen, it is murder.

We come now to those kinds of killing in which the Law, from the second method of reasoning we have spoken of, implies malice, and into which slaying of others, those unfortunate persons of whom we speak in the following sheets were mostly led either through the violence of their passions, or through the necessity into which they are often drawn by the commission of thefts and other crimes. Thus, were a person to kill another in doing a felony, though it be by accident, or where a person fires at one who resists his robbing him and by such firing kills another against whom he had no design, yet from the evil intention of the first act, he becomes liable for all its consequences, and the fact, by an implication of malice, will be adjudged murder. Nay, though there be no design of committing felony, but only of breaking the peace, yet if a man be slain in the tumult they will all be guilty of murder, because their first act was a deliberate breach of the Law. There is yet another manner of killing which the Law punishes with the utmost severity, which is resisting an officer, civil or criminal, in the execution of his office (arresting a person) so that he be slain, yet though he did not produce his warrant, the offence will be adjudged murder. And if persons who design no mischief at all, do unadvisedly commit any idle wanton act which cannot but be attended with manifest danger, such as riding with a horse known to kick amongst a crowd of people, merely to divert oneself by putting them in a fright, and by such riding a death ensues, there such a person will be judged guilty of murder. Yet some offences there are of so transcendent a cruelty that the Law hath thought fit to difference them from the other murders, and these are of three sorts, viz., where a servant kills his master; where a wife kills her husband; where an ecclesiastical man kills his prelate to whom he owes obedience. In all these cases the Law makes the crimes Petit Treason.

From crimes committed against the lives of men we descend next to offences against their goods, in which, that we may be the more clearly understood, we shall begin with the lowest kind of thefts. The Law calls it larceny where there is felonious and fraudulent taking and carrying away the mere personal goods of another, so long as it be neither from his person nor out of his house. If the value of such goods be under twelvepence, then it is called petty larceny, and is punishable only by whipping or other corporal punishments; but if they exceed that value, then it is grand larceny, and is punishable with death, where benefit of clergy is not allowed.

There are a multitude of offences contained under the general title of grand larceny, and, therefore, as I intend only to give my readers such a general idea of Crown Law as may serve to render the following pages more intelligible, so I shall dwell on such particulars as are more especially useful in that respect, and leave the perfect knowledge of the pleas of the Crown to be attained by the study of the several books which treat of them directly and fully. There was until the reign of King William, a doubt whether a lodger who stole the furniture of his lodgings were indictable as a felon, inasmuch as he had a special property in the goods, and was to pay the greater rent in consideration of them. To clear this, a Statute was made in the afore-mentioned reign, by which it is declared larceny and felony for any person to steal, embezzle, or purloin any chattel or furniture which by contract he was to have the use of in lodging; and by a Statute made in the reign of Henry VIII, it is enacted that all servants being of the age of eighteen years, and not apprentices, to whom goods and chattels shall be delivered by their masters or mistresses for them to keep, if they shall go away with, or shall defraud or embezzle any part of such goods or chattels, to the value of forty shillings or upwards, then such false and fraudulent act be deemed and adjudged felony.

But besides simple larceny, which is divided into grand and petty, there is a mixed larceny which has a greater degree of guilt in it, as being a taking from the person of a man or from his house. Larceny from the person of a man either puts him in fear, and then it is a robbery, or does not put him in fear, and then it is a larceny from the person, and of this we shall speak first. It is either committed without a man's knowledge, and in such a case it is excluded from benefit of clergy, or it is openly done before the person's face, and then it is within the benefit of clergy, unless it be in a dwelling-house and to the value of forty shillings, in which case benefit is taken away by an Act made in the reign of the late Queen. Larceny from the house is at this day in several cases excluded from benefit of clergy, but in others it is allowed.

Robbery is the taking away violently and feloniously the goods or money from the person of a man, putting him in fear; and this taking is not only with the robber's own hands, but if he compel, by the terror of his assault, the person whom he robs to give it himself, or bind him by such terrible oaths, that afterwards in conscience he thinks himself obliged to give it, is a taking within the Law, and cannot be purged from any delivery afterwards. Yea, where there is a gang of several persons, only one of which robs, they are all guilty as to the circumstance of putting in fear, wherever a person attacks another with circumstances of terror, as though fear oblige him to part with his money though it be without weapons drawn, and the person taking it pretend to receive it as an alms. And in respect of punishment, though judgment of death cannot be given in any larceny whatsoever, unless the goods taken exceed twelve pence in value, yet in robbery such judgment is given, let the value of the goods be ever so small.

As to crimes committed against the habitations of men, there are two kinds, viz., burglary and arson.

Burglary is a felony at Common Law, and consists in breaking and entering the mansion house of another in the night time with an intent of committing a felony therein, whether that intention be executed or not. Here, from the best opinions, is to be understood such a degree of darkness as hinders a man's countenance from being discerned. The breaking and entering are points essential to be proved in order to make any fact burglary; the place in which it is committed must be a dwelling house, and the breaking and entering such a dwelling house must be an intent of committing felony, and not a trespass; and this much I think is sufficient to define the nature of this crime, which notwithstanding the many examples which have been made of it, is still too much practised. As to arson, by which the Law understand maliciously and voluntarily burning the house of another by night or by day; to make a man guilty of this it must appear that he did it voluntarily and of malice aforethought.

Besides these, there are several other felonies which are made so by Statute, such as rapes committed on women by force, and against their will. This offence was anciently punished by putting out the eyes and cutting off the testicles of the offenders; it was afterwards made a felony, and by a statute in Queen Elizabeth's reign, excluded from benefit of clergy. By an Act made in the reign of King Henry the Seventh, taking any woman (whether maid, wife or widow) having any substance, or being heir apparent to her ancestors, for the lucre of such substance, and either to marry or defile the said woman against her will, then such persons and all those procuring or abetting them in the said violence, shall be guilty of felony, from which, by another Act in Queen Elizabeth's reign, benefit of clergy is taken. Also by an Act in the reign of King James the First, any person marrying, their former husband or wife being then alive, such persons shall be deemed guilty of felony, but benefit of clergy is yet allowed for this offence.

As it often happens that boisterous and unruly people, either in frays or out of revenge, do very great injuries unto others, yet without taking away their lives, in such a case the Law adjudges the offender who commits a mayhem to the severest penalties. The true definition of a mayhem is such a hurt whereby a man is rendered less able in fighting, so that cutting off or disabling a man's hand, striking out his eye, or foretooth, were mayhems at Common Law. But by the Statute of King Charles the Second, if any person or persons, with malice aforethought, by lying in wait, unlawfully cut out or disable the tongue, put out an eye, slit the nose, or cut off the nose or lip of any subject of his Majesty, with an intention of maiming or disfiguring, then the person so offending, their counsellors, aiders and abetters, privy to the offence, shall suffer death, as in cases of felony, without benefit of clergy; which Act is commonly called the Coventry Act, because it was occasioned by the slitting of the nose of a gentleman of that name, for a speech made by him in Parliament.[1]

As nothing is of greater consequence to the commonwealth than public credit, so the Legislature hath thought fit, by the highest punishments, to deter persons from committing such facts for the lucre of gain, as might injure the credit of the nation. For this purpose, an Act was made in the reign of the late King William, by which forging or counterfeiting the common seal of the Governor and Company of the Bank of England, or of any sealed bank-bill given out in the name of the said Governor and Company for the payment of any sum of money, or of any bank-note whatsoever, signed by the said Governor and Company of the Bank of England, or altering or raising any bank-bill, or note of any sort, is declared to be felony, without benefit of clergy. Upon this Statute there have been several convictions, and it is hoped men are pretty well cured of committing this crime, by that care those in the direction of the Bank have always taken to bring offenders of this kind to justice.

By an Act also passed in the reign of King William, persons who counterfeit any stamp which by its mark relates to the Revenue, shall be guilty of felony without benefit of clergy, and upon this also there have been some executions.

But as the public companies established in this kingdom have often occasion to borrow money under their common seal, which bonds, so sealed, are transferable and pass currently from hand to hand as ready money, so for the greater security of the subject the counterfeiting the common seal of the South Sea Company, or altering any bond or obligation of the said company, is rendered felony without benefit of clergy. Some other statutes of the same nature in respect to lottery tickets, etc., have been made to create felonies of the counterfeiting thereof, but of these and some other later Statutes, I forbear mentioning here, because I have spoken particularly of them in the cases where persons have been punished for transgressing them.

As I have already exceeded the bounds which I at first intended should have restrained my Preface, so I forbear lengthening it in speaking of lesser crimes, few of which concern the persons whose lives are to be found in the following volume. Therefore I shall conclude here, only putting my readers once more in mind that by this work the intent of the Law, in punishing malefactors, is more perfectly fulfilled, since the example of their deaths is transmitted in a proper light to posterity.

Sir John Coventry, M. P. for Weymouth, in the course of a debate on a proposed levy on playhouses, asked "whether did the king's pleasure lie among the men or the women that acted?" This open allusion to Charles's relations with Nell Gwynn and Moll Davies enraged the Court party, and on Dec. 21, 1670, as Sir John was going to his house in Suffolk Street, he was waylaid by a brutal gang under Sir Thomas Sandys, dragged from his carriage, and his nose slit to the bone. This outrage caused great indignation, and the Coventry Act mentioned in the text was passed, 22 & 23 Car. II. The perpetrators of the deed escaped.

Passion, when it once gains an ascendant over our minds, is often more fatal to us than the most deliberate course of vice could be. On every little start it throws us from the paths of reason, and hurries us in one moment into acts more wicked and more dangerous than we could at any other time suffer to enter our imagination. As anger is justly said to be a short madness, so, while the frenzy is upon us, blood is shed as easily as water, and the mind is so filled with fury that there is no room left for compassion. There cannot be a stronger proof of what I have been observing than in the unhappy end of the poor woman who is the subject of this chapter.

Jane Griffin was the daughter of honest and substantial parents, who educated her with very great tenderness and care, particularly with respect to religion, in which she was well and rationally instructed. As she grew up her person grew agreeable, and she had a lively wit and a very tolerable share of understanding. She lived with a very good reputation, and to general satisfaction, in several places, till she married Mr. Griffin, who kept the Three Pigeons in Smithfield[2].

She behaved herself so well and was so obliging in her house that she drew to it a very great trade, in which she managed so as to leave everyone well satisfied. Yet she allowed her temper to fly out into sudden gusts of passion, and that folly alone sullied her character to those who were witnesses of it, and at last caused a shameful end to an honest and industrious life.

One Elizabeth Osborn, coming to live with her as a servant, she proved of a disposition as Mrs. Griffin could by no means agree with. They were continually differing and having high words, in which, as is usual on such occasions, Mrs. Griffin made use of wild expressions, which though she might mean nothing by them when she spoke them, yet proved of the utmost ill consequence, after the fatal accident of the maid's death. For being then given in evidence, they were esteemed proofs of malice prepense, which ought to be a warning to all hasty people to endeavour at some restraint upon their tongues when in fits of anger, since we are not only sure of answering hereafter for every idle word we speak, but even here they may, as in this case, become fatal in the last degree.

It was said at the time those things were transacted that jealousy was in some degree the source of their debates, but of that I can affirm nothing. It no way appeared as to the accident which immediately drew on her death, and which happened after this manner.

One evening, having cut some cold fowl for the children's supper, it happened the key of the cellar was missing on a sudden, and on Mrs. Griffin's first speaking of it they began to look for it. But it not being found, Mrs. Griffin went into the room where the maid was, and using some very harsh expression, taxed her with having seen it, or laid it out of the way. Instead of excusing herself modestly, the maid flew out also into ill language at her mistress, and in the midst of the fray, the knife with which she had been cutting lying unluckily by her, she snatched it up, and stuck it into the maid's bosom; her stays happening to be unluckily open, it entered so deep as to give her a mortal wound.

After she had struck her Mrs. Griffin went upstairs, not imagining that she had killed her, but the alarm was soon raised on her falling down, and Mrs. Griffin was carried before a magistrate, and committed to Newgate. When she was first confined, she seemed hopeful of getting off at her trial, yet though she did not make any confession, she was very sorrowful and concerned. As her trial drew nearer, her apprehensions grew stronger, till notwithstanding all she could urge in her defence, the jury found her guilty, and sentence was pronounced as the Law directs.

Hitherto she had hopes of life, and though she did not totally relinquish them even upon her conviction, yet she prepared with all due care for her departure. She sent for the minister of her own parish, who attended her with great charity, and she seemed exceedingly penitent and heartily sorry for her crime, praying with great favour and emotion.

And as the struggling of an afflicted heart seeks every means to vent its sorrow, in order to gain ease, or at least an alleviation of pain, so this unhappy woman, to soothe the gloomy sorrows that oppressed her, used to sit down on the dirty floor, saying it was fit she should humble herself in dust and ashes, and professing that if she had an hundred hearts she would freely yield them all to bleed, so they might blot out the stain of her offence. By such expression did she testify those inward sufferings which far exceed the punishment human laws inflict, even on the greatest crimes.

When the death warrant came down and she utterly despaired of life, her sorrow and contrition became greater than before, and here the use and comfort of religion manifestly appeared; for had not her faith in Christ moderated her afflictions, perhaps grief might have forestalled the executioner, but she still comforted herself with thinking on a future state, and what in so short an interval she must do to deserve an happy immortality.

The time of her death drawing very near, she desired a last interview with her husband and daughter, which was accompanied with so much tenderness that nobody could have beheld it without the greatest emotion. She exhorted her husband with great earnestness to the practice of a regular and Christian life, begged him to take due care of his temporal concerns, and not omit anything necessary in the education of the unhappy child she left behind her. When he had promised a due regard should be had to all her requests she seemed more composed and better satisfied than she had been. Continuing her discourse, she reminded him of what occurred to her with regard to his affairs, adding that it was the last advice she should give, and begging therefore it might be remembered. She finished what she had to say with the most fervent prayers and wishes for his prosperity.

Turning next to her daughter, and pouring over her a flood of tears, My dearest child, she said, let the afflictions of thy mother be a warning and an example unto thee; and since I am denied life to educate and bring thee up, let this dreadful monument of my death suffice to warn you against yielding in any degree to your passion, or suffering a vehemence of temper to transport you so far even as indecent words, which bring on a custom of flying out in a rage on trivial occasions, till they fatally terminate in such acts of wrath and cruelty as that for which I die. Let your heart, then, be set to obey your Maker and yield a ready submission to all His laws. Learn that Charity, Love and Meekness which our blessed religion teaches, and let your mother's unhappy death excite you to a sober and godly life. The hopes of thus are all I have to comfort me in this miserable state, this deplorable condition to which my own rash folly has reduced me.

The sorrow expressed both by her husband and by her child was very great and lively and scarce inferior to her own, but the ministers who attended her fearing their lamentations might make too strong an impression on her spirits, they took their last farewell, leaving her to take care of her more important concern, the eternal welfare of her soul.

Some malicious people (as is too often the custom) spread stories of this unfortunate woman, as if she had been privy to the murder of one Mr. Hanson, who was killed in the Farthing-Pie House fields[3]; and attended this with so many odd circumstances and particulars, which tales of this kind acquire by often being repeated, that the then Ordinary of Newgate thought it became him to mention it to the prisoner. Mrs. Griffin appeared to be much affected at her character being thus stained by the fictions of idle suspicions of silly mischievous persons. She declared her innocence in the most solemn manner, averred she had never lived near the place, nor had heard so much as the common reports as to that gentleman's death.

Yet, as if folks were desirous to heap sorrow on sorrow, and to embitter even the heavy sentence on this poor woman, they now gave out a new fable to calumniate her in respect to her chastity, averring on report of which the first author is never to be found, that she had lived with Mr. Griffin in a criminal intimacy before their marriage. The Ordinary also (though with great reluctance) told her this story. The unhappy woman answered it was false, and confirmed what she said by undeniable evidence, adding she freely forgave the forgers of so base an insinuation.

When the fatal day came on which she was to die, Mrs. Griffin endeavoured, as far as she was able, to compose herself easily to submit to what was not now to be avoided. She had all along manifested a true sense of religion, knowing that nothing could support her under the calamities she went through but the hopes of earthly sufferings atoning for her faults, and becoming thereby a means of eternal salvation. Yet though these thoughts reconciled this ignominious death to her reason, her apprehensions were, notwithstanding, strong and terrible when it came so near.

At the place of execution she was in terrible agonies, conjuring the minister who attended her and the Ordinary of Newgate, to tell her whither there was any hopes of her salvation, which she repeated with great earnestness, and seeming to part with them reluctantly. The Ordinary entreated her to submit cheerfully to this, her last stage of sorrow, and in certain assurance of meeting again (if it so pleased God) in a better slate.

The following paper having been left in the hands of a friend, and being designed for the people, I thought proper to publish it.

I declare, then, with respect to the deed for which I die, that I did it without any malice or anger aforethought, for the unlucky instrument of my passion lying at hand, when first words arose on the loss of the key, I snatched it up suddenly, and executed that rash act which hath brought her and me to death, without thinking.

I trust, however, that my most sincere and hearty repentance of this bloody act of cruelty, the sufferings which I have endured since, the ignominious death I am now to die, and above all the merits of my Saviour, who shed His blood for me on the Cross, will atone for this my deep and heavy offence, and procure for me eternal rest.

But as I am sensible that there is no just hope of forgiveness from the Almighty without a perfect forgiveness of those who have any way injured us, so I do freely and from the bottom of my soul, forgive all who have ever done me any wrong, and particularly those who, since my sorrowful imprisonment, have cruelly aspersed me, earnestly entreating all who in my life-time I may have offended, that they would also in pity to my deplorable state, remit those offences to me with a like freedom.

And now as the Law hath adjudged, and I freely offer my body to suffer for what I have committed, I hope nobody will be so unjust and so uncharitable as to reflect on those I leave behind me on my account, and for this, I most humbly make my last dying request, as also that ye would pray for my departed soul.

She died with all exterior marks of true penitence, being about forty years of age, the 29th of January, 1719-20.

This tavern was in Butcher Hall Lane (now King Edward Street, Newgate Street), and was a favourite resort of the Paternoster Row booksellers.

The Farthing-Pie House was a tavern in Marylebone. It was subsequently re-christened The Green Man.

The first of these offenders had been an old sinner, and I suppose had acquired the nickname of the Golden Tinman as a former practitioner in the same wretched calling did that of the Golden Farmer.[4] Trippuck had robbed alone and in company for a considerable space, till his character was grown so notorious that some short time before his being taken for the last offence, he had, by dint of money and interest, procured a pardon. However, venturing on the deed which brought him to his death, the person injured soon seized him, and being inexorable in his prosecution, Trippuck was cast and received sentence. However, having still some money, he did not lose all hope of a reprieve, but kept up his spirits by flattering himself with his life being preserved, till within a very few days of the execution. If the Ordinary spoke to him of the affairs of the soul, Trippuck immediately cut him short with, D'ye believe I can obtain a pardon? I don't know that, indeed, says the doctor. But you know one Counsellor Such-a-one, says Trippuck, prithee make use of your interest with him, and see whether you can get him to serve me. I'll not be ungrateful, doctor.

The Ordinary was almost at his wits' end with this sort of cross purposes; however, he went on to exhort him to think of the great work he had to do, and entreated him to consider the nature of that repentance which must atone for all his numerous offences. Upon this, Trippuck opened his breast and showed him a great number of scars amongst which were two very large ones, out of which he said two musket bullets had been extracted. And will not these, good doctor, quoth he, and the vast pains I have endured in their cure, in some sort lessen the heinousness of the facts I may have committed? No, said the Ordinary, what evils have fallen upon you in such expeditions, you have drawn upon yourself, and do not imagine that these will in any degree make amends for the multitude of your offences. You had much better clear your conscience by a full and ingenious confession of your crimes, and prepare in earnest for another world, since I dare assure you, you need entertain no hopes of staying in this.

As soon as be found the Ordinary was in the right, and that all expectation of a reprieve or pardon were totally in vain, Trippuck began, as most of those sort of people do, to lose much of that stubbornness they mistake for courage. He now felt all the terrors of an awakened conscience, and persisted no longer in denying the crime for which he died, though at first he declared it altogether a falsehood, and Constable, his companion, had denied it even to death. As is customary when persons are under their misfortune, it had been reported that this Trippuck was the man who killed Mr. Hall towards the end of the summer before on Blackheath, but when the story reached the Golden Tinman's ears he declared it was an utter falsity; repeating this assertion to the Ordinary a few moments before his being turned off, and pointing to the rope about him, he said, As you see this instrument of death about me, what I say is the real truth. He died with all outward signs of penitence.

Richard Cane was a young man of about twenty-two years of age, at the time he suffered. Having a tolerable genius when a youth, his friends put him apprentice twice, but to no purpose, for having got rambling notions in his head, he would needs go to sea. There, but for his unhappy temper, he might have done well, for the ship of war in which he sailed was so fortunate as to take, after eight hours sharp engagement, a Spanish vessel of immense value; but the share he got did him little service. As soon as he came home Richard made a quick hand of it, and when the usual train of sensual delights which pass for pleasures in low life had exhausted him to the last farthing, necessity and the desire of still indulging his vices, made him fall into the worst and most unlawful methods to obtain the means which they might procure them.

Sometime after this, the unhappy man of whom we are speaking fell in love (as the vulgar call it) with an honest, virtuous, young woman, who lived with her mother, a poor, well-meaning creature, utterly ignorant of Cane's behaviour, or that he had ever committed any crimes punishable by Law. The girl, as such silly people are wont, yielded quickly to a marriage which was to be consummated privately, because Cane's relations were not to be disobliged, who it seems did not think him totally ruined so long as he escaped matrimony. But the unhappy youth not having enough money to procure a licence, and being ashamed to put the expense on the woman and her mother, in a fit of amorous distraction went out from them one evening, and meeting a man somewhat fuddled in the street, threw him down, and took away his hat and coat. The fellow was not so drunk but that he cried out, and people coming to his assistance, Cane was immediately apprehended, and so this fact, instead of raising him money enough to be married, brought him to death in this ignominious way.

While he lay in Newgate, the miserable young creature who was to have been his wife came constantly to cry with him and deplore their mutual misfortunes, which were increased by the girl's mother falling sick, and being confined to her bed through grief for her designed son-in-law's fate. When the day of his suffering drew on, this unhappy man composed himself to submit to it with great serenity. He professed abundance of contrition for the wickedness of his former life and lamented with much tenderness those evils he had brought upon the girl and her mother. The softness of his temper, and the steady affection he had for the maid, contributed to make his exit much pitied; which happened at Tyburn in the twenty-second year of his age. He left this paper behind him, which he spoke at the tree.

Good People,

The Law having justly condemned me for my offence to suffer in this shameful manner, I thought it might be expected that I should say something here of the crime for which I die, the commission of which I do readily acknowledge, though it was attended with that circumstance of knocking down, which was sworn against me. I own I have been guilty of much wickedness, and am exceedingly troubled at the reflection it may bring upon my relations, who are all honest and reputable people. As I die for the offences I have done, and die in charity forgiving all the world, so I hope none will be so cruel as to pursue my memory with disgrace or insult an unhappy young woman on my account, whose character I must vindicate with my last breath, as all the justice I am able to do her, I die in the communion of the Church of England and humbly request your prayers for my departing soul.

Richard Shepherd was born of very honest and reputable parents in the city of Oxford, who were careful in giving him a suitable education, which he, through the wickedness of his future life, utterly forgot, insomuch that he knew scarce the Creed and the Lord's Prayer, at the time he had most need of them. When he grew a tolerable big lad his friends put him out as apprentice to a butcher, where having served a great part of his time, he fell in love, as they call it, with a young country lass hard by, and Dick's passion growing outrageous, he attacked the poor maid with all the amorous strains of gallantry he was able. The hearts of young uneducated wenches, like unfortified towns, make little resistance when once beseiged, and therefore Shepherd had no great difficulty in making a conquest. However the girl insisted on honourable terms, and unfortunately for the poor fellow they were married before his time was out; an error in conduct, which in low life is seldom retrieved.

It happened so here. Shepherd's master was not long before he discovered this wedding. He thereupon gave the poor fellow so much trouble that he was at last forced to give him forty shillings down, and a bond for twenty-eight pounds more. This having totally ruined him, Dick unhappily fell into the way of dishonest company, who soon drew him into their ways of gaining money and supplying his necessities at the hazard both of his conscience and his neck; in which, though he became an expert proficient, yet could he never acquire anything considerable thereby, but was continually embroiled in debt. His wife bringing every year a child, contributed not a little thereto. However, Dick rubbed on mostly by thieving and as little by working as it was possible to avoid.

When he first began his robberies, he went housebreaking, and actually committed several facts in the city of Oxford itself. But those things not being so easily to be concealed there as at London, report quickly began to grow very loud about him, and Dick was forced to make shift with pilfering in other places; in which he was (to use the manner of speaking of those people) so unlucky that the second or third fact he committed in Hertfordshire, he was detected, seized, and at the next assizes capitally convicted. Yet out of compassion to his youth, and in hopes he might be sufficiently checked by so narrow an escape from the gallows, his friends procured him first a reprieve and then a pardon.

But this proximity to death made little impression on his heart, which is too often the fault in persons who, like him, receive mercy, and have notwithstanding too little grace to make use of it. Partly driven by necessity, for few people cared after his release to employ him, partly through the instigations of his own wicked heart, Dick went again upon the old trade for which he had so lately been like to have suffered, but thieving was still an unfortunate profession to him. He soon after fell again into the hands of Justice, from whence he escaped by impeaching Allen and Chambers, two of his accomplices, and so evaded Tyburn a second time. Yet all this signified nothing to him, for as soon as he was at home, so soon to work he went in his old way, till apprehended and executed for his wickedness.

No unhappy criminal had more warning than Shepherd of his approaching miserable fate, if he would have suffered anything to have deterred him; but alas! what are advices, terrors, what even the sight of death itself, to souls hardened in sin and consciences so seared as his. He had, when taken up and carried before Col. Ellis, been committed to New Prison for a capital offence. He had not remained there long before he wrote the Colonel a letter in which (provided he were admitted an evidence) he offered to make large discoveries. His offers were accepted, and several convicted capitally at the Old Bailey by him were executed at Tyburn, whither for his trade of housebreaking, Shepherd quickly followed them.

While in Newgate Shepherd had picked up a thoughtless resolution as to dying, not uncommon to those malefactors who, having been often condemned, go at last hardened to the gallows. When he was exhorted to think seriously of making his peace with God, he replied 'twas done and he was sure of going to Heaven.

With these were executed Thomas Charnock, a young man well and religiously educated. By his friends he had been placed in the house of a very eminent trader, and being seduced by ill-company yielded to the desire of making a show in the world. In order to do so, he robbed his master's counting-house, which fact made him indeed conspicuous, but in a very different manner from what he had flattered himself with. They died tolerably submissive and penitent, this last malefactor, especially, having rational ideas of religion.

William Davis, the Golden Farmer, was a notorious highwayman, who obtained his sobriquet from a habit of always paying in gold. He was hanged in Fleet Street, December 20, 1689. His adventures are told at length in Smith's History of the Highwaymen, edited by me and published in the same series as this volume.

This William Barton was born in Thames Street, London, and seemed to have inherited a sort of hereditary wildness and inconstancy, his father having been always of a restless temper and addicted to every species of wickedness, except such as are punished by temporal laws. While this son William was a child, he left him, without any provision, to the care of his mother, and accompanied by a concubine whom he had long convened with, shipped himself for the island of Jamaica, carrying with him a good quantity of goods proper for that climate, intending to live there as pleasantly as the place would give him leave. His head being well turned, both for trading and planting, it was, indeed, probable enough he should succeed.

Now, no sooner was his father gone on this unaccountable voyage, but William was taken home and into favour by his grandfather, who kept a great eating-house in Covent Garden. Here Will, if he would, might certainly have done well. His grandfather bound him to himself, treated him with the utmost tenderness and indulgence, and the gentlemen who frequented the house were continually making him little presents, which by their number were considerable, and might have contented a youth like him.

But William, whose imagination was full of roving as his father's, far from sitting down pleased and satisfied with that easy condition into which Fortune had thrown him, began to dream of nothing but travels and adventures. In short, in spite of all the poor old man, his grandfather, could say to prevent it, to sea he went, and to Jamaica in quest of his father, who he fancied must have grown extravagantly rich by this time, the common sentiments of fools, who think none poor who have the good luck to dwell in the West Indies.

On Barton's arrival at Jamaica he found all things in a very different condition from what he had flattered himself with. His father was dead and the woman who went over with him settled in a good plantation, 'tis true, but so settled that Will was unable to remove her; so he betook himself to sea again, and rubbed on the best way he was able. But as if the vengeance of Heaven had pursued him, or rather as if Providence, by punishments, designed to make him lay aside his vices, Barton had no sooner scraped a little money together, but the vessel in which he sailed was (under the usual pretence of contraband goods) seized by the Spaniards, who not long after they were taken, sent the men they made prisoners into Spain. The natural moroseness of those people's temper, makes them harsh masters. Poor Barton found it so, and with the rest of his unfortunate companions, suffered all the inconveniences of hard usage and low diet, though as they drew nearer the coast of Spain that severity was a little softened.

When they were safely landed, they were hurried to a prison where it was difficult to determine which was worst, their treatment or their food. Above all the rest Barton was uneasy, and his head ever turned towards contriving an escape. When he and some other intriguing heads had meditated long in vain, an accident put it in their power to do that with ease which all their prudence could not render probable in the attempt, a thing common with men under misfortune, who have reason, therefore, never to part with hope.

Finding an old wall in the outer court of the prison weak, and ready to fall down, the keeper caused the English prisoners, amongst others, to be sent to repair it. The work was exceedingly laborious, but Barton and one of his companions soon thought of a way to ease it. They had no sooner broke up a small part of the foundation which was to be new laid, but stealing the Spanish soldiers' pouches, they crowded the powder into a small bag, placing it underneath as far as they could reach, and then gave it fire. This threw up two yards of the wall, and while the Spaniards stood amazed at the report, Barton and his associates marched off through the breach, without finding the slightest resistance from any of the keeper's people, though he had another party in the street.

But this would have signified very little, if Providence had not also directed them to a place of safety by bringing them as soon as they broke out of the door to a monastery. Thither they fled for shelter, and the religious of the place treated them with much humanity. They succoured them with all necessary provision, protected them when reclaimed by the gaoler, and taking them into their service, showed them in all respects the same care and favour they did to the rest of their domestics.

Yet honest labour, however recompensed, was grating to these restless people, who longed for nothing but debauchery, and struggled for liberty only as a preparative to the indulging of their vices; and so they began to contrive how they should free themselves from hence. Barton and his fellow engineer were not long before they fell on a method to effect it, by wrenching open the outer doors in the night, and getting to an English vessel that lay in the harbour ready to sail.

They had not been aboard long ere they found that the charitable friars had agreed with the captain for their passage, and so all they gained by breaking out was the danger of being reclaimed, or at least going naked and without any assistance, which to be sure they would have met with from their masters, if they could but have had a little patience. But the passion of returning home, or rather a vehement lust after the basest pleasures, hurried them to whatever appeared conducive to that end, however fatal in its consequence it might be.

When they were got safe into their native country again, each took such a course for a livelihood as he liked best. Whether Barton then fell into thievery, or whether he learned not that mystery before he had served an apprenticeship thereto in the Army I cannot say, but in some short space after his being at home 'tis certain that he listed himself a soldier, and served several campaigns in Flanders, during the last War. Being a very gallant fellow, he gained the love of his officers, and there was great probability of his doing well there, having gained at least some principle of honour in the service, which would have prevented him doing such base things as those for which he afterwards died. But, unhappily for him, the War ended just as he was on the point of becoming paymaster-sergeant, and his regiment being disbanded, poor Will became broke in every acceptation of the word. He retained always a strong tincture of his military education, and was peculiarly fond of telling such adventures as he gained the knowledge of, while in the Army.

Amongst other stories that he told were one or two which may appear perhaps not unentertaining to my readers. When Brussels came towards the latter end of the War to be pretty well settled under the Imperialists, abundance of persons of distinction came to reside there and in the neighborhood from the advantage natural to so fine a situation. Amongst these was the Baron De Casteja, a nobleman of a Spanish family, who except for his being addicted excessively to gaming, was in every way a fine gentlemen. He had married a lady of one of the best families in Flanders, by whom he had a son of the greatest hopes. The baron's passion for play had so far lessened their fortune that they lived but obscurely at a village three leagues from Brussels, where having now nothing to support his gaming expenses, he grew reformed, and his behaviour gained so high and general esteem that the most potent lord in the country met not with higher reverence on any occasion. The great prudence and economy of the baroness made her the theme of general praise, while the young Chevalier de Casteja did not a little add to the honours of the family.

It happened the baron had a younger brother in the Emperor's service, whose merit having raised him to a considerable rank in his armies, he had acquired a very considerable estate, to the amount of upwards of one hundred thousand crowns, which on his death he bequeathed him. Upon this accession of fortune, the Baron Casteja, as is but too frequent, fell to his old habit, and became as fond of gaming as ever. The poor lady saw this with the utmost concern, and dreaded the confounding this legacy, as all the baron's former fortune had been consumed by his being the dupe of gamesters. In deep affliction at the consideration of what might in future times become the Chevalier's fortune, she therefore entreated the baron to lay out part of the sum in somewhat which might be a provision for his son. The baron promised both readily and faithfully that he would out of the first remittance. A few weeks later he received forty thousand crowns and the baroness and he set out for Brussels, under pretence of enquiring for something proper for his purpose, carrying with him twenty thousand crowns for the purchase. But he forgot the errand upon the road, and no sooner arrived at Brussels, but going to a famous marquis's entertainment, in a very few hours lost the last penny of his money. Returning home after this misfortune, he was a little out of humour for a week, but at the end of that space, making up the other twenty thousand privately he intended to set out next day.

The poor lady, at her wit's end for fear this large sum should go the same way as the other, bethought herself of a method of securing both the cash and her son's place. She communicated her design to her major domo, who readily came into it, and having taken three of the servants and the baroness's page into the secret, he sent for Barton and another Englishman quartered near them, and easily prevailed on them for a very small sum, to become accomplices in the undertaking. In a word, the lady having provided disguises for them, and a man's suit for herself, caused the touch-holes of the arms which the baron and two servants carried with him to be nailed up, and then towards evening sallying at the head of her little troop from a wood, as he passed on the road, the baron being rendered incapable of resistance, was robbed of the whole twenty thousand crowns. With this she settled her son, and the baron was so far touched at the loss of such a provision for his family, that he made a real and thorough reformation, and Barton from this exploit fell in love with robbing ever after.