Title: Far Off; Or, Asia and Australia Described

Author: Favell Lee Mortimer

Release date: July 24, 2004 [eBook #13011]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Project Gutenberg Distributed Proofreaders from page images provided by the Internet Archive Children's Library and the University of Florida

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Far Off, by Favell Lee Mortimer

In the Frontispiece may be seen an English lady, who went to live upon Mount Sion to teach little Jewesses and little Mahomedans to know the Saviour. That lady has led three of her young scholars to a plain just beyond the gates of Jerusalem; and while two of them are playing together, she is listening to little Esther, a Jewess of eight years old. The child is fond of sitting by her friend, and of hearing about the Son of David. She has just been singing,

and now she is saying, "O, ma'am, that's sweet! Jesus Christ is our Redeemer, our Redeemer: no man can redeem his brother, no money,—nothing—but only the precious blood of Christ."

This little work pleads for the notice of parents and teachers on the same grounds as its predecessor, "Near Home."

Its plea is not completeness, nor comprehensiveness, nor depth of research, nor splendor of description; but the very reverse,—its simple, superficial, desultory character, as better adapted to the volatile beings for whom it is designed.

Too long have their immortal minds been captivated by the adventures and achievements of knights and princesses, of fairies and magicians; it is time to excite their interest in real persons, and real events. In childhood that taste is formed which leads the youth to delight in novels, and romances; a taste which has become so general, that every town has its circulating library, and every shelf in that library is filled with works of fiction.

While these fascinating inventions are in course of perusal, many a Bible is unopened, or if opened, hastily skimmed; many a seat in church is unoccupied, or if occupied, the service, and the sermon disregarded—so intense is the sympathy of the novel reader with his hero, or his heroine.

And what is the effect of the perusal? Many a young mind, inflated with a desire for admiration and adventure, grows tired of home, impatient of restraint, indifferent to simple pleasures, and averse to sacred instructions. How important, therefore, early to endeavor to prevent a taste for FICTION, by cherishing a taste for FACTS.

But this is not the only aim of the present work; it seeks also to excite an interest in those facts which ought most to interest immortal beings—facts relative to souls, and their eternal happiness—to God, and his infinite glory.

These are the facts which engage the attention of the inhabitants of heaven. We know not whether the births of princes, and the coronations of monarchs are noticed by the angelic hosts; but we do know that the repentance of a sinner, be he Hindoo or Hottentot, is celebrated by their melodious voices in rapturous symphonies.

Therefore "Far Off" desire to interest its little readers in the labors of missionaries,—men despised and maligned by the world, but honored and beloved by the SAVIOUR of the world. An account of the scenery and natives of various countries, is calculated to prepare the young mind for reading with intelligence those little Missionary Magazines, which appear every month, written in so attractive a style, and adorned with such beautiful illustrations. Parents have no longer reason to complain of the difficulty of finding sacred entertainment for their children on Sunday, for these pleasing messengers,—if carefully dealt out,—one or two on each Sabbath, would afford a never failing supply.

To form great and good characters, the mind must be trained to delight in TRUTH,—not in comic rhymes, in sentimental tales, and skeptical poetry. The truth revealed in God's Holy Word, should constitute the firm basis of education; and the works of Creation and Providence the superstructure while the Divine blessing can alone rear and cement the edifice.

Parents, train up your children to serve God, and to enjoy his presence forever; and if there be amongst them—an EXTRAORDINARY child, train him up with extraordinary care, lest instead of doing extraordinary good he should do extraordinary evil, and be plunged into extraordinary misery.

Train up—the child of imagination—not to dazzle, like Byron, but to enlighten, like Cowper: the child of wit—not to create profane mirth, like Voltaire, but to promote holy joy, like Bunyan: the child of reflection—not to weave dangerous sophistries, like Hume, but to wield powerful arguments, like Chalmers: the child of sagacity—not to gain advantages for himself, like Cromwell, but for his country, like Washington: the child of eloquence—not to astonish the multitude, like Sheridan, but to plead for the miserable, like Wilberforce: the child of ardor—not to be the herald of delusions, like Swedenbourg, but to be the champion of truth, like Luther: the child of enterprise—not to devastate a Continent, like the conquering Napoleon, but to scatter blessings over an Ocean, like the missionary Williams:—and, if the child be a prince,—train him up—not to reign in pomp and pride like the fourteenth Louis, but to rule in the fear of God, like our own great ALFRED.

Of all the countries in the world which would you rather see?

Would it not be the land where Jesus lived?

He was the Son of God: He loved us and died for us.

What is the land called where He lived? Canaan was once its name: but now Palestine, or the Holy Land.

Who lives there now?

Alas! alas! The Jews who once lived there are cast out of it. There are some Jews there; but the Turks are the lords over the land. You know the Turks believe in Mahomet.

What place in the Holy Land do you wish most to visit?

Some children will reply, Bethlehem, because Jesus was born there; another will answer, Nazareth, because Jesus was brought up there; and another will say, "Jerusalem," because He died there.

I will take you first to

A good minister visited this place, accompanied by a train of servants, and camels, and asses.

It is not easy to travel in Palestine, for wheels are never seen there, because the paths are too steep, and rough, and narrow for carriages.

Bethlehem is on a steep hill, and a white road of chalk leads up to the gate. The traveller found the streets narrow, dark, and dirty. He lodged in a convent, kept by Spanish monks. He was shown into a large room with carpets and cushions on the floor. There he was to sleep. He was led up to the roof of the house to see the prospect. He looked, and beheld the fields below where the shepherds once watched their flocks by night: and far off he saw the rocky mountains where David once hid himself from Saul.

But the monks soon showed him a more curious sight. They took him into their church, and then down some narrow stone steps into a round room beneath. "Here," said they, "Jesus was born." The floor was of white marble, and silver lamps were burning in it. In one corner, close to the wall, was a marble trough, lined with blue satin. "There," said the monks, "is the manger where Jesus was laid." "Ah!" thought the traveller, "it was not in such a manger that my Saviour rested his infant head; but in a far meaner place."

These monks have an image of a baby, which they call Jesus. On Christmas-day they dress it in swaddling-clothes and lay it in the manger: and then fall down and worship it.

The next day, as the traveller was ready to mount his camel, the people of Bethlehem came with little articles which they had made. But he would not buy them, because they were images of the Virgin Mary and her holy child, and little white crosses of mother-of-pearl. They were very pretty: but they were idols, and God hates idols.

Here our Lord was crucified.

Is there any child who does not wish to hear about it?

The children of Jerusalem once loved the Lord, and sang his praises in the temple. Their young voices pleased their Saviour, though not half so sweet as angels' songs.

Which is the place where the temple stood?

It is Mount Moriah. There is a splendid building there now.

Is it the temple? O no, that was burned many hundreds of years ago. It is the Mosque of Omar that you see; it is the most magnificent mosque in all the world. How sad to think that Mahomedans should worship now in the very spot where once the Son of God taught the people. No Jew, no Christian may go into that mosque. The Turks stand near the gate to keep off both Jews and Christians.

Every Friday evening a very touching scene takes place near this mosque. There are some large old stones there, and the Jews say they are part of their old temple wall: so they come at the beginning of their Sabbath (which is on Friday evening) and sit in a row opposite the stones. There they read their Hebrew Old Testaments, then kneel low in the dust, and repeat their prayers with their mouths close to the old stones: because they think that all prayers whispered between the cracks and crevices of these stones will be heard by God. Some Jewesses come, wrapped from head to foot in long white veils, and they gently moan and softly sigh over Jerusalem in ruins.

What Jesus said has come to pass, "Behold, your house is left unto you desolate." The thought of this sad day made Jesus weep, and now the sight of it makes the Jews weep.

But there is a place still dearer to our hearts than Mount Moriah. It is Calvary. There is a church there: but such a church! a church full of images and crosses. Roman Catholics worship there—and Greeks too: and they often fight in it, for they hate one another, and have fierce quarrels.

That church is called "The Church of the Holy Sepulchre." It is pretended that Christ's tomb or sepulchre is in it. Turks stand at the door and make Christians pay money before they will let them in.

When they enter, what do they see?

In one corner a stone seat. "There," say the monks, "Jesus sat when He was crowned with thorns." In another part there is a stone pillar. "There," say the monks, "He was scourged." There is a high place in the middle of the church with stairs leading up to it. When you stand there the monks say, "This is the top of Calvary, where the cross stood." But we know that the monks do not speak the truth, for the Romans destroyed Jerusalem soon after Christ's crucifixion, and no one knows the very place where He suffered.

On Good Friday the monks carry all round the church an image of the Saviour as large as life, and they fasten it upon a cross, and take it down again, and put it in the sepulchre, and they take it out again on Easter Sunday. How foolish and how wrong are these customs! It was not in this way the apostles showed their love to Christ, but by preaching his word.

Mount Zion is the place where David brought the ark with songs and music. There is a church where the Gospel is preached and prayers are offered up in Hebrew, (the Jew's language.) The minister is called the Bishop of Jerusalem. He is a Protestant. A few Jews come to the church at Mount Zion, and some have believed in the Lord Jesus.

And there is a school there where little Jews and Jewesses and little Mahomedans sit side by side while a Christian lady teaches them about Jesus. In the evening, after school, she takes them out to play on the green grass near the city. A little Jewess once much pleased this kind teacher as she was sitting on a stone looking at the children playing. Little Esther repeated the verse—

and then she said very earnestly, "O, ma'am, how sweet to think that Jesus is our Redeemer. No man can redeem his brother: no money—no money can do it—only the precious blood of Jesus Christ." Little Esther seemed as if she loved Jesus, as those children did who sang his praises in the temple so many years ago.

But there is another place—very sad, but very sweet—where you must come. Go down that valley—cross that small stream—(there is a narrow bridge)—see those low stone walls—enter: it is the Garden of Gethsemane. Eight aged olive-trees are still standing there; but Jesus comes there no more with his beloved disciples. What a night was that when He wept and prayed—when the angel comforted Him—and Judas betrayed Him.

The mountain just above Gethsemane is the Mount of Olives. Beautiful olive-trees are growing there still. There is a winding path leading to the top. The Saviour trod upon that Mount just before he was caught up into heaven. His feet shall stand there again, and every eye shall see the Saviour in his glory. But will every eye be glad to see Him?

O no; there will be bitter tears then flowing from many eyes.

And what kind of a city is Jerusalem?

It is a sad and silent city. The houses are dark and dirty, the streets are narrow, and the pavement rough. There are a great many very old Jews there. Jews come from all countries when they are old to Jerusalem, that they may die and be buried there. Their reason is that they think that all Jews who are buried in their burial-ground at Jerusalem will be raised first at the last day, and will be happy forever. Most of the old Jews are very poor: though money is sent to them every year from the Jews in Europe.

There are also a great many sick Jews in Jerusalem, because it is such an unhealthy place. The water in the wells and pools gets very bad in summer, and gives the ague and even the plague. Good English Christians have sent a doctor to Jerusalem to cure the poor sick people. One little girl of eleven years old came among the rest—all in rags and with bare feet: she was an orphan, and she lived with a Jewish washerwoman. The doctor went to see the child in her home. Where was it? It was near the mosque, and the way to it was down a narrow, dark passage, leading to a small close yard. The old woman lived in one room with her grandchildren and the orphan: there was a divan at each end, that is, the floor was raised for people to sleep on. The orphan was not allowed to sleep on the divans, but she had a heap of rags for her bed in another part. The child's eyes glistened with delight at the sight of her kind friend the doctor, he asked her whether she went to school. This question made the whole family laugh: for no one in Jerusalem teaches girls to read except the kind Christian lady I told you of.

The most gloomy and horrible place in the Holy Land is the Dead Sea. In that place there once stood four wicked cities, and God destroyed them with fire and brimstone.

You have heard of Sodom and Gomorrah.

A clergyman who went to visit the Dead Sea rode on horseback, and was accompanied by men to guard him on the way, as there are robbers hid among the rocks. He took some of the water of the Dead Sea in his mouth, that he might taste it, and he found it salt and bitter; but he would not swallow it, nor would he bathe in it.

He went next to look at the River Jordan. How different a place from the dreary, desolate Dead Sea! Beautiful trees grow on the banks, and the ends of the branches dip into the stream. The minister chose a part quite covered with branches and bathed there, and as the waters went over his head, he thought, "My Saviour was baptized in this river." But he did not think, as many pilgrims do who come here every year, that his sins were washed away by the water: no, he well knew that Christ's blood alone cleanses from sin. There is a place where the Roman Catholics bathe, and another where the Greeks bathe every year; they would not on any account bathe in the same part, because they disagree so much.

After drinking some of the sweet soft water of Jordan, the minister travelled from Jericho to Jerusalem. He went the very same way that the good Samaritan travelled who once found a poor Jew lying half-killed by thieves. Even to this day thieves often attack travellers in these parts: because the way is so lonely, and so rugged, and so full of places where thieves can hide themselves.

A horse must be a very good climber to carry a traveller along the steep, rough, and narrow paths, and a traveller must be a bold man to venture to go to the edge of the precipices, and near the robbers' caves.

In the midst of Palestine is the well where the Lord spoke so kindly to the woman of Samaria. In the midst of a beautiful valley there is a heap of rough stones: underneath is the well. But it is not easy to drink water out of this well. For the stone on the top is so heavy, that it requires many people to remove it: and then the well is deep, and a very long rope is necessary to reach the water. The clergyman (of whom I have spoken so often) had nothing to draw with; therefore, even if he could have removed the stone, he could not have drunk of the water. The water must be very cool and refreshing, because it lies so far away from the heat. That was the reason the Samaritan woman came so far to draw it: for there were other streams nearer the city, but there was no water like the water of Jacob's well.

The city where that woman lived was called Sychar. It is still to be seen, and it is still full of people. You remember that the men of that city listened to the words of Jesus, and perhaps that is the reason it has not been destroyed. The country around is the most fruitful in all Canaan; there are such gardens of melons and cucumbers, and such groves of mulberry-trees.

How different from Sychar is Capernaum! That was the city where Jesus lived for a long while, where he preached and did miracles. It was on the borders of the lake of Genesareth. The traveller inquired of the people near the lake, where Capernaum once stood; but no one knew of such a place: it is utterly destroyed. Jesus once said, "Woe unto Capernaum." Why? Because it repented not.

The lake of Genesareth looked smooth as glass when the traveller saw it; but he heard that dreadful storms sometimes ruffled those smooth waters. It was a sweet and lovely spot; not gloomy and horrible like the Dead Sea. The shepherds were there leading their flocks among the green hills where once the multitude sat down while Jesus fed them.

Not very far off is the city where Jesus lived when he was a boy.

NAZARETH.—All around are rugged rocky hills. In old times it was considered a wicked city; perhaps it got this bad name from wicked people coming here to hide themselves: and it seems just fit for a hiding-place. From the top of one of the high crags the Nazarenes once attempted to hurl the blessed Saviour.

There is a Roman Catholic convent there, where the minister lodged. He was much disturbed all day by the noise in the town; not the noise of carts and wagons, for there are none in Canaan, but of screaming children, braying asses, and grunting camels. One of his servants came to him complaining that he had lost his purse with all his wages. He had left it in his cell, and when he came back it was gone. Who could have taken it? It was clear one of the servants of the convent must have stolen it, for one of them had the key of the room. The travellers went to the judge of the town to complain; but the judge, who was a Turk, was asleep, and no one was allowed to awake him. In the evening, when he did awake, he would not see justice done, because he said he had nothing to do with the servants at the convent, as they were Christians. Nazareth, you see, is still a wicked city, where robbery is committed and not punished.

There is much to make the traveller sad as he wanders about the Holy Land.

That land was once fruitful, but now it is barren. It is not surprising that no one plants and sows in the fields, because the Turks would take away the harvests.

Once it was a peaceful land, but now there are so many enemies that every man carries a gun to defend himself.

Once it was a holy land, but now Mahomet is honored, and not the God of Israel.

When shall it again be fruitful, and peaceful, and holy? When the Jews shall repent of their sins and turn to the Lord. Then, says the prophet Ezekiel, (xxxvi. 35,) "They shall say, This land that was desolate is become like the garden of Eden."[1]

Taken chiefly from "A Pastor's Memorial," by the Rev. George Fisk.

Those who love the Holy Land will like to hear about Syria also; for Abraham lived there before he came into Canaan. Therefore the Israelites were taught to say when they offered a basket of fruit to God, "A Syrian was my father." It was a heathen land in old times; and it is now a Mahomedan land; though there are a few Christians there, but very ignorant Christians, who know nothing of the Bible.

Syria is a beautiful land, and famous for its grand mountains, called Lebanon. The same clergyman who travelled through the Holy Land went to Lebanon also. He had to climb up very steep places on horseback, and slide down some, as slanting as the roof of a house. But the Syrian horses are very sure-footed. It is the custom for the colts from a month old to follow their mothers; and so when a rider mounts the back of the colt's mother, the young creature follows, and it learns to scramble up steep places, and to slide down; even through the towns the colt trots after its mother, and soon becomes accustomed to all kinds of sights and sounds: so that Syrian horses neither shy nor stumble.

The traveller was much surprised at the dress of the women of Lebanon: for on their heads they wear silver horns sticking out from under their veils, the strangest head-dress that can be imagined.

There are sweet flowers growing on the sides of Lebanon; but at the top there are ice and snow.

The traveller ate some ice, and gave some to the horses; and the poor beasts devoured it eagerly, and seemed quite refreshed by their cold meal.

The snow of Lebanon is spoken of in the Bible as very pure and refreshing. "Will a man leave the snow of Lebanon, which cometh from the rock of the field?"—Jer. xviii. 14.

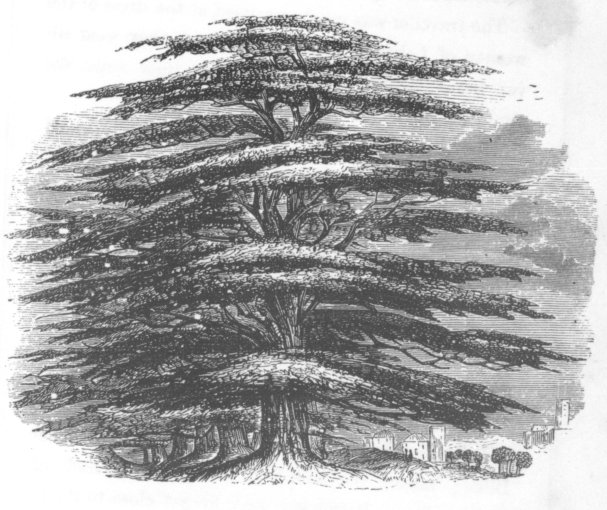

The traveller earnestly desired to behold the cedars of Lebanon: for a great deal is said about them in the Bible; indeed, the temple of Solomon was built of those cedars. It was not easy to get close to them; for there were craggy rocks all around: but at last the traveller reached them, and stood beneath their shade. There were twelve very large old trees, and their boughs met at the top, and kept off the heat of the sun. These trees might be compared to holy men, grown old in the service of God: for this is God's promise to his servants,—"The righteous shall flourish like the palm-tree: he shall grow like a cedar in Lebanon."—Psalm xc. 11, 12.

This is the capital of Syria.

It is perhaps the most ancient city in the world. Even in the time of Abraham, Damascus was a city; for his servant Eliezer came from it.

But Damascus is most famous, on account of a great event which once happened near it. A man going towards that city suddenly saw in the heavens a light brighter than the sun, and heard a voice from on high, calling him by his name. Beautiful as the city was, he saw not its beauty as he entered it, for he had been struck blind by the great light. That man was the great apostle Paul.

Who can help thinking of him among the gardens of fruit-trees surrounding Damascus?

The damask rose is one of the beauties of Damascus. There is one spot quite covered with this lovely red rose.

I will now give an account of a visit a stranger paid to a rich man in Damascus. He went through dull and narrow streets, with no windows looking into the streets. He stopped before a low door, and was shown into a large court behind the house. There was a fountain in the midst of the court, and flower-pots all round. The visitor was then led into a room with a marble floor, but with no furniture except scarlet cushions. To refresh him after his journey, he was taken to the bath. There a man covered him with a lather of soap and water, then dashed a quantity of hot water over him, and then rubbed him till he was quite dry and warm.

When he came out of the bath, two servants brought him some sherbet. It is a cooling drink made of lemon-juice and grape-juice mixed with water.

The master of the house received the stranger very politely: he not only shook hands with him, but afterwards he kissed his own hand, as a mark of respect to his guest. The servants often kissed the visitor's hand.

The dinner lasted a long while, for only one dish was brought up at a time. Of course there were no ladies at the dinner, for in Mahomedan countries they are always hidden. There were two lads there, who were nephews to the master of the house; and the visitor was much surprised to observe that they did not sit down to dinner with the company; but that they stood near their uncle, directing the servants what to bring him; and now and then presenting a cup of wine to him, or his guests. But it is the custom in Syria for young people to wait upon their elders; however, they may speak to the company while they are waiting upon them.

Damascus used to be famous for its swords: but now the principal things made there, are stuffs embroidered with silver, and boxes of curious woods, as well as red and yellow slippers. The Syrians always wear yellow slippers, and when they walk out they put on red slippers over the yellow. If you want to buy any of the curious works of Damascus, you must go to the bazaars in the middle of the town; there the sellers sit as in a market-place, and display their goods.

SCHOOLS.—It is not the custom in Syria for girls to learn to read. But a few years ago, a good Syrian, named Assaad, opened a school for little girls as well as for boys.

It was easy to get the little boys to come; but the mothers did not like to send their little girls. They laughed, and said, "Who ever heard of a girl going to school? Girls need not learn to read." The first girl who attended Assaad's school was named Angoul, which means "Angel." Where is the child that deserves such a name? Nowhere; for there is none righteous, no, not one. Angoul belonged not to Mahomedan parents, but to those called Christians; yet the Christians in Syria are almost as ignorant as heathens.

Angoul had been taught to spin silk; for her father had a garden of mulberry-trees, and a quantity of silk worms. She was of so much use in spinning, that her mother did not like to spare her: but the little maid promised, that if she might go to school, she would spin faster than ever when she came home. How happy she was when she obtained leave to go! See her when the sun has just risen, about six o'clock, tripping to school. She is twelve years old. Her eyes are dark, but her hair is light. Angoul has not been scorched by the sun, like many Syrian girls, because she has sat in-doors at her wheel during the heat of the day. She is dressed in a loose red gown, and a scarlet cap with a yellow handkerchief twisted round it like a turban.

At school Angoul is very attentive, both while she is reading in her Testament, and while she is writing on her tin slate with a reed dipped in ink. She returns home at noon through the burning sun, and comes to school again to stay till five. Then it is cool and pleasant, and Angoul spins by her mother's side in the lovely garden of fruit-trees before the house. Has she not learned to sing many a sweet verse about the garden above, and the heavenly husbandman? As she watches the budding vine, she can think now of Him who said, "I am the true vine." As she sits beneath the olive-tree, she can call to mind the words, "I am like a green olive-tree in the house of my God." Angoul is growing like an angel, if she takes delight in meditating on the word of God.[2]

Extracted chiefly from the Rev. George Fisk's "Pastor's Memorial," and Kinnear's Travels.

This is the land in which the Israelites wandered for forty years. You have heard what a dry, dreary, desert place the wilderness was. There is still a wilderness in Arabia; and there are still wanderers in it; not Israelites, but Arabs. These men live in tents, and go from place to place with their large flocks of sheep and goats. But there are other Arabs who live in towns, as we do.

Do you know who is the father of the Arabs?

The same man who is the father of the Jews.

What, was Abraham their father?

Yes, he was.

Do you remember Abraham's ungodly son, Ishmael?

He was cast out of his father's house for mocking his little brother Isaac, and he went into Arabia.

And what sort of people are the Arabs?

Wild and fierce people.

Travellers are afraid of passing through Arabia, lest the Arabs should rob and murder them; and no one has ever been able to conquer the Arabs. The Arabs are very proud, and will not bear the least affront. Sometimes one man says to another, "The wrong side of your turban is out." This speech is considered an affront never to be forgotten. The Arabs are so unforgiving and revengeful that they will seek to kill a man year after year. One man was observed to carry about a small dagger. He said his reason was, he was hoping some day to meet his enemy and kill him.

Of what religion are this revengeful people? The Mahomedan.

Mahomed was an Arab. It is thought a great honor to be descended from him. Those men who say Mahomed is their father wear a green turban, and very proud they are of their green turbans, even though they may only be beggars.

THE ARABIAN WOMEN.—They are shut up like the women in Syria when they live in towns, but the women in tents are obliged to walk about; therefore they wear a thick veil over their face, with small holes for their eyes to peep out.

The poor women wear a long shirt of white or blue; but the rich women wrap themselves in magnificent shawls. To make themselves handsome, they blacken their eyelids, paint their nails red, and wear gold rings in their ears and noses. They delight in fine furniture. A room lined with looking-glasses, and with a ceiling of looking-glasses, is thought charming.

ARAB TENTS.—They are black, being made of the hair of black goats. Some of them are so large that they are divided into three rooms, one for the cattle, one for the men, and one for the women.

ARAB CUSTOMS.—The Arabs sit on the ground, resting on their heels, and for tables they have low stools. A large dish of rice and minced mutton is placed on the table, and immediately every hand is thrust into it; and in a moment it is empty. Then another dish is brought, and another; and sometimes fourteen dishes of rice, one after the other, till all the company are satisfied. They eat very fast, and each retires from dinner as soon as he likes, without waiting for the rest. After dinner they drink water, and a small cup of coffee without milk or sugar. Then they smoke for many hours.

The Arabs do not indulge in eating or drinking too much, and this is one of the best parts of their character.

THE THREE EVILS OF ARABIA.

The first evil is want of water. There is no river in Arabia: and the small streams are often dried up by the heat.

The second evil is many locusts, which come in countless swarms, and devour every green thing.

The third evil is the burning winds. When a traveller feels it coming, he throws himself on the ground, covering his face with his cloak, lest the hot sand should be blown up his nostrils. Sometimes men and horses are choked by this sand.

These are the three great evils; but there is a still greater, the religion of Mahomed: for this injures the soul; the other evils only hurt the body.

THE THREE ANIMALS OF ARABIA.

The animals for which Arabia is famous are animals to ride upon.

Two of them are often seen in England; though here they are not nearly as fine as in Arabia; but the third animal is never used in England. Most English boys have ridden upon an ass. In Arabia the ass is a handsome and spirited creature. The horse is strong and swift, and yet obedient and gentle. The camel is just suited to Arabia. His feet are fit to tread upon the burning sands; because the soles are more like India-rubber than like flesh: his hard mouth, lined with horn, is not hurt by the prickly plants of the desert; and his hump full of fat is as good to him as a bag of provisions: for on a journey the fat helps to support him, and enables him to do with very little food. Besides all this, his inside is so made that he can live without water for three days.

A dromedary is a swifter kind of camel, and is just as superior to a camel as a riding-horse is to a cart-horse.

THE THREE PRODUCTIONS OF ARABIA.

These are coffee, dates, and gums.

For these Arabia is famous.

The coffee plants are shrubs. The hills are covered with them; the white blossoms look beautiful among the dark green leaves, and so do the red berries.

The dates grow on the palm-trees; and they are the chief food of the Arabs. The Arabs despise those countries where there are no dates.

There are various sweet-smelling gums that flow from Arabian trees.

THE THREE PARTS OF ARABIA.

You see from what I have just said that there are plants and trees in Arabia. Then it is clear that the whole land is not a desert. No, it is not; there is only a part called Desert Arabia; that is on the north. There is a part in the middle almost as bad, called Stony Arabia, yet some sweet plants grow there; but there is a part in the south called Happy Arabia, where grow abundance of fragrant spices, and of well-flavored coffee.

THE THREE CITIES OF ARABIA.

Arabia has long been famous for three cities, called Mecca, Medina, and Mocha.

Mecca is considered the holiest city in the world. And why? Because the false prophet Mahomed was born there. On that account Mahomedans come from all parts of the world to worship in the great temple there. Sometimes Mecca is as full of people as a hive is full of bees.

Of all the cities in the East, Mecca is the gayest, because the houses have windows looking into the streets. In these houses are lodgings for the pilgrims.

And what is it the pilgrims worship?

A great black stone, which they say the angel Gabriel brought down from heaven as a foundation for Mahomed's house. They kiss it seven times, and after each kiss they walk round it.

Then they bathe in a well, which they say is the well the angel showed to Hagar in the desert, and they think the waters of this well can wash away all their sins. Alas! they know not of the blood which can wash away all sin.

Medina contains the tomb of Mahomed; yet it is not thought so much of as Mecca. Perhaps the Mahomedans do not like to be reminded that Mahomed died like any other man, and never rose again.

Mocha.—This is a part whence very fine coffee is sent to Europe.

TRAVELS IN THE DESERT.

Of all places in Arabia, which would you desire most to see? Would it not be Mount Sinai? Our great and glorious God once spoke from the top of that mountain.

I will tell you of an English clergyman who travelled to see that mountain. As he knew there were many robbers on the way, he hired an Arab sheikh to take care of him. A sheikh is a chief, or captain. Suleiman was a fine-looking man, dressed in a red shirt, with a shawl twisted round his waist, a purple cloak, and a red cap. His feet and legs were bare. His eyes were bright, his skin was brown, and his beard black. To his girdle were fastened a huge knife and pistols, and by his side hung a sword. This man brought a band of Arabs with him to defend the travellers from the robbers in the desert.

One day the whole party set out mounted on camels. After going some distance, a number of children were seen scampering among the rocks, and looking like brown monkeys. These were the children of the Arabs who accompanied the Englishman. The wild little creatures ran to their fathers, and saluted them in the respectful manner that Arab children are taught to do.

At last a herd of goats was seen with a fine boy of twelve years old leading them. He was the son of Suleiman. The father seemed to take great delight in this boy, and introduced him to the traveller. The kind gentleman riding on a camel, put down his hand to the boy. The little fellow, after touching the traveller's hand, kissed his own, according to the Arabian manner.

The way to Mount Sinai was very rough; indeed, the traveller was sometimes obliged to get off his camel, and to climb among the crags on hands and knees. How glad he was when the Arabs pointed to a mountain, and said, "That is Mount Sinai." With what fear and reverence he gazed upon it! Here it was that the voice of the great God was once heard speaking out of the midst of the smoke, and clouds, and darkness!

How strange it must be to see in this lonely gloomy spot, a great building! Yet there is one at the foot of the mountain. What can it be? A convent. See those high walls around. It is necessary to have high walls, because all around are bands of fierce robbers. It is even unsafe to have a door near the ground. There is a door quite high up in the wall; but what use can it be of, when there are no steps by which to reach it? Can you guess how people get in by this door? A rope is let down from the door to draw the people up. One by one they are drawn up. In the inside of the walls there are steps by which travellers go down into the convent below. The monks who live there belong to the Greek church.

The clergyman was lodged in a small cell spread with carpets and cushions, and he was waited upon by the monks.

These monks think that they lead a very holy life in the desert. They eat no meat, and they rise in the night to pray in their chapel. But God does not care for such service as this. He never commanded men to shut themselves up in a desert, but rather to do good in the world.

One day the monks told the traveller they would show him the place where the burning bush once stood. How could they know the place? However, they pretended to know it. They led the way to the chapel, then taking off their shoes, they went down some stone steps till they came to a round room under ground, with three lamps burning in the midst. "There," said the monks, "is the very spot where the burning bush once stood."

There were two things the traveller enjoyed while in the convent, the beautiful garden full of thick trees and sweet flowers; and the cool pure water from the well. Such water and such a garden in the midst of a desert were sweet indeed.

The Arabs, who accompanied the traveller, enjoyed much the plentiful meals provided at the convent; for the monks bought sheep from the shepherds around, to feed their guests. After leaving the convent, Suleiman was taken ill in consequence of having eaten too much while there. The clergyman gave him medicine, which cured him. The Arabs were very fond of their chief, and were so grateful to the stranger for giving him in medicine, that they called him "the good physician." Suleiman himself showed his gratitude by bringing his own black coffee-pot into the tent of the stranger, and asking him to drink coffee with him; for such is the pride of an Arab chief, that he thinks it is a very great honor indeed for a stranger to share his meal.

But the traveller soon found that it is dangerous to pass through a desert. Why? Not on account of wild beasts, but of wild men. There was a tribe of Arabs very angry with Suleiman, because he was conducting the travellers through their part of the desert. They wanted to be the guides through that part, in hopes of getting rewarded by a good sum of money. You see how covetous they were. The love of money is the root of all evil.

These angry Arabs were hidden among the rocks and hills; and every now and then they came suddenly out of their hiding-places, and with a loud voice threatened to punish Suleiman.

How much alarmed the travellers were! but none more than Suleiman himself. He requested the clergyman to travel during the whole night, in order the sooner to get out of the reach of the enemy. The clergyman promised to go as far as he was able. What a journey it was! No one durst speak aloud to his companions, lest the enemies should be hidden among the rocks close by, and should overhear them. At midnight the whole company pitched their tents by the coast of the Red Sea. Early in the morning the minister went alone to bathe in its smooth waters. After he had bathed, and when he was just going to return to the tents, he was startled by hearing the sound of a gun. The sound came from the midst of a small grove of palm-trees close by. Alarmed, he ran back quickly to the tents: again he heard the report of a gun: and again a third time. The travellers, Arabs and all, were gathered together, expecting an enemy to rush out of the grove. But where was Suleiman? He had gone some time before into the grove of palm-trees to talk to the enemies.

Presently the traveller saw about forty Arabs leave the grove and go far away. But Suleiman came not. So the minister went into the grove to search for him, and there he found—-not Suleiman—but his dead body!

There it lay on the ground, covered with blood. The minister gazed upon the dark countenance once so joyful, and he thought it looked as if the poor Arab had died in great agony. It was frightful to observe the number of his wounds. Three balls had been shot into his body by the gun which went off three times. Three great cuts had been made in his head; his neck was almost cut off from his head, and his hand from his arm! How suddenly was the proud Arab laid low in the dust! All his delights were perished forever. Suleiman had been promised a new dress of gay colors at the end of the journey; but he would never more gird a shawl round his active frame, or fold a turban round his swarthy brow. The Arabs wrapped their beloved master in a loose garment, and placing him on his beautiful camel, they went in deep grief to a hill at a little distance. There they buried him. They dug no grave; but they made a square tomb of large loose stones, and laid the dead body in the midst, and then covered it with more stones. There Suleiman sleeps in the desert. But the day shall come when "the earth shall disclose her blood, and shall no more cover her slain:" and then shall the blood of Suleiman and his slain body be uncovered, and his murderer brought to judgment.[3]

Extracted chiefly from "The Pastor's Memorial," by the Rev. G. Fisk. Published by R. Carter & Brothers.

Is there a Turkey in Asia as well as a Turkey in Europe?

Yes, there is; and it is governed by the same sultan, and filled by the same sort of persons. All the Turks are Mahomedans.

You may know a Mahomedan city at a distance. When we look at a Christian city we see the steeples and spires of churches; but when we look at a Mahomedan city we see rising above the houses and trees the domes and minarets of mosques. What are domes and minarets? A dome is the round top of a mosque: and the minarets are the tall slender towers. A minaret is of great use to the Mahomedans.

Do you see the little narrow gallery outside the minaret. There is a man standing there. He is calling people to say their prayers. He calls so loud that all the people below can hear, and the sounds he utters are like sweet music. But would it not make you sad to hear them when you remembered what he was telling people to do? To pray to the god of Mahomet, not to the God and Father of the Lord Jesus Christ; but to a false god: to no God. This man goes up the dark narrow stairs winding inside the minaret five times a day: first he goes as soon as the sun rises, then at noon, next in the afternoon, then at sunset, and last of all in the night. Ascending and descending those steep stairs is all his business, and it is hard work, and fatigues him very much.

In the court of the mosque there is a fountain. There every one washes before he goes into the mosque to repeat his prayers, thinking to please God by clean hands instead of a clean heart. Inside the mosque there are no pews or benches, but only mats and carpets spread on the floor. There the worshippers kneel and touch the ground with their foreheads. The minister of the mosque is called the Imam. He stands in a niche in the wall, with his back to the people, and repeats prayers.

But he is not the preacher. The sheikh, or chief man of the town, preaches; not on Sunday, but on Friday. He sits on a high place and talks to the people—not about pardon and peace, and heaven and holiness—but about the duty of washing their hands before prayers, and of bowing down to the ground, and such vain services.

In the mosque there are two rows of very large wax candles, much higher than a man, and as thick as his arm, and they are lighted at night.

It is considered right to go to the mosque for prayers five times a day; but very few Mahomedans go so often. Wherever people may be, they are expected to kneel down and repeat their prayers, whether in the house or in the street. But very few do so. While they pray, Mahomedans look about all the time, and in the midst speak to any one, and then go on again; for their hearts are not in their prayers; they do not worship in spirit and in truth.

There are no images or pictures in the mosques, because Mahomet forbid his followers to worship idols. There are Korans on reading stands in various parts of the mosque for any one to read who pleases.

The people leave their red slippers at the door, keeping on their yellow boots only; but they do not uncover their heads as Christians do.

Was Christ ever known in this Mahomedan land? Yes, long before he was known in England. Turkey in Asia used to be called Asia Minor, (or Asia the less,) and there it was that Paul the apostle was born, and there he preached and turned many to Christ. But at last the Christians began to worship images, and the fierce Turks came and turned the churches into mosques. This was the punishment God sent the Christians for breaking his law. In some of the mosques you may see the marks of the pictures which the Christians painted on the walls, and which the Turks nearly scraped off.

How dreadful it would be if our churches should ever be turned into mosques! May God never send us this heavy punishment.

One corner of Turkey in Asia is called Armenia. There are many high mountains in Armenia, and one of them you would like to see very much. It is the mountain on which Noah's ark rested after the flood. I mean Ararat.[4]

It is a very high mountain with two peaks; and its highest peak is always covered with snow. People say that no one ever climbed to the top of that peak. I should think Noah's ark rested on a lower part of the mountain between the two peaks, for it would have been very cold for Noah's family on the snow-covered peak, and it would have been very difficult for them to get down. How pleasant it must be to stand on the side of Ararat, and to think, "Here my great father Noah stood, and my great mother, Noah's wife; here they saw the earth in all its greenness, just washed with the waters of the flood, and here they rejoiced and praised God."

I am glad to say that all the Armenians are not Mahomedans. Many are Christians, but, alas! they know very little about Christ except his name. I will tell you a short anecdote to show how ignorant they are.

Once a traveller went to see an old church in Armenia called the Church of Forty Steps, because there are forty steps to reach it: for it is built on the steep banks of a river.

The traveller found the churchyard full of boys. This churchyard was their school-room. And what were their books? The grave-stones that lay flat upon the ground. Four priests were teaching the boys. These priests wore black turbans; while Turkish Imams wear white turbans. One of these Armenian priests led the traveller to an upper room, telling him he had something very wonderful to show him. What could it be? The priest went to a nacho in the wall and took out of it a bundle; then untied a silk handkerchief, and then another, and then another; till he had untied twenty-five silk handkerchiefs. What was the precious thing so carefully wrapped up? It was a New Testament.

It is a precious book indeed: but it ought to be read, and not wrapped up. The priest praised it, saying, "This is a wonderful book; it has often been laid upon sick persons, and has cured them." Then a poor old man, bent and tottering, pressed forward to kiss the book, and to rub his heavy head. This was worshipping the book, instead of Him who wrote it.

An Armenian village looks like a number of molehills: for the dwellings are holes dug in the ground with low stone walls round the holes; the roof is made of branches of trees and heaps of earth. There are generally two rooms in the hole—one for the family, and one for the cattle.

A traveller arrived one evening at such a village; and he was pleased to see fruit-trees overshadowing the hovels, and women, without veils, spinning cotton under their shadow. But he was not pleased with the room where he was to sleep. The way lay through a long dark passage under ground; and the room was filled with cattle: there was no window nor chimney. How dark and hot it was! Yet it was too damp to sleep out of doors, because a large lake was near; therefore he wrapped his cloak around him, and lay upon the ground; but he could not sleep because of the stinging of insects, and the trampling of cattle: and glad he was in the morning to breathe again the fresh air.

Rich Armenians have fine houses. Once a traveller dined with a rich Armenian. The dinner was served up in a tray, and placed on a low stool, while the company sat on the ground. One dish after another was served up till the traveller was tired of tasting them. But there was not only too much to eat; there was also too much to drink. Rakee, a kind of brandy, was handed about; and afterwards a musician came in and played and sang to amuse the company. In Turkey there is neither playing, nor singing, nor drinking spirits. The Turks think themselves much better than Christians. "For," say they, "we drink less and pray more." They do not know that real Christians are not fond of drinking, and are fond of praying; only they pray more in secret, and the Turks more in public.

The fiercest of all the people in Asia are the Kurds.

They are the terror of all who live near them.

Their dwellings are in the mountains; there some live in villages, and some in black tents, and some in strong castles. At night they rush down from the mountains upon the people in the valleys, uttering a wild yell, and brandishing their swords. They enter the houses, and begin to pack up the things they find, and to place them on the backs of their mules and asses, while they drive away the cattle of the poor people; and if any one attempts to resist them, they kill him. You may suppose in what terror the poor villagers live in the valleys. They keep a man to watch all night, as well as large dogs; and they build a strong tower in the midst of the village where they run to hide themselves when they are afraid.

The reason why the Armenians live in holes in the ground is because they hope the Kurds may not find out where they are.

Those Kurds who live in tents often move from place to place. The black tents are folded up and placed on the backs of mules; and a large kettle is slung upon the end of the tent-pole. The men and women drive the herds and flocks, while the children and the chickens ride upon the cows.

The Kurds have thin, dark faces, hooked noses, and black eyes, with a fierce and malicious look.

They are of the Mahomedan religion, and the call to prayers may be heard in the villages of these robbers and murderers.

This country is part of Turkey in Asia. It lies between two very famous rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates, often spoken of in the Bible. The word Mesopotamia means "between rivers." It was between these rivers that faithful Abraham lived when God first called him to be his friend. Should you not like to see that country? It is now full of ruins. The two most ancient cities in the world were built on the Tigris and Euphrates.

Nineveh was on the Tigris.

What a city that was at the time Jonah preached there! Its walls were so thick that three chariots could go on the top all abreast.

But what is Nineveh now? Look at those green mounds. Under those heaps of rubbish lies Nineveh. A traveller has been digging among those mounds, and has found the very throne of the kings of Nineveh, and the images of winged bulls and lions which adorned the palace. God overthrew Nineveh because it was wicked.

There is another ancient city lying in ruins on the Euphrates, it is Babylon the Great.

There are nothing but heaps of bricks to be seen where once proud Babylon stood. Where are now the streets fifteen miles long? Where are the hanging gardens? Gardens one above the other, the wonder of the world? Where is now the temple of Belus, (or of Babel, as some think,) with its golden statue? All, all are now crumbled into rubbish. God has destroyed Babylon as he said.

There are dens of wild beasts among the ruins. A traveller saw some bones of a sheep in one, the remains, he supposed, of a lion's dinner; but he did not like to go further into the den to see who dwelt there. Owls and bats fill all the dark places. But no men live there, though human bones are often found scattered about, and they turn into dust as soon as they are touched.

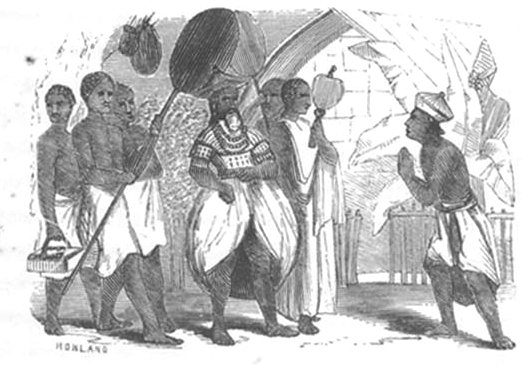

There is now a great city in Mesopotamia, called Bagdad. In Babylon no sound is heard but the howlings of wild beasts; in Bagdad men may be heard screaming and hallooing from morning to night. The drivers of the camels and the mules shout as they press through the narrow crooked streets, and even the ladies riding on white donkeys, and attended by black slaves, scream and halloo.

In summer it is so hot in Bagdad that people during the day live in rooms under ground, and sleep on their flat roofs at night.

It is curious to see the people who have been sleeping on the roof get up in the morning. First they roll up their mattrasses, their coverlids, and pillows, and put them in the house. The children cannot fold up theirs, but their mothers or black slaves do it for them. The men repeat their prayers, and then drink a cup of coffee, which their wives present to them. The wives kneel as they offer the cup to their lords, and stand with their hands crossed while their lords are drinking, then kneel down again to receive the cup, and to kiss their lords' hand. Then the men take their pipes, and lounge on their cushions, while the women say their prayers. And when do the children say their prayers? Never. They know only of Mahomet; they know not the Saviour who said, "Suffer little children to come unto me."

It is remarkable that this mountain lies at the point where three great empires meet, namely, Russia, Persia, and Turkey.

Is this country mentioned in the Bible? Yes; we read of Cyrus, the king of Persia. Isaiah spoke of him before he was born, and called him by his name. See chapter xlv.

Persia is now a Mahomedan country. The Turks, you remember, are Mahomedans too. Perhaps you think those two nations, the Turks and the Persians, must agree well together, as they are of the same religion. Far from it. No nations hate one another more than Turks and Persians do; and the reason is, that though they both believe in Mahomet, they disagree about his son-in law, Ali. The Persians are very fond of him, and keep a day of mourning in memory of his death; whereas the Turks do not care for Ali at all.

But is this a reason why they should hate one another so much?

Even in their common customs the Persians differ from the Turks. The Turks sit cross-legged on the ground; the Persians sit upon their heels. Which way of sitting should you prefer? I think you would find it more comfortable to sit like a Turk.

The Turks sit on sofas and lean against cushions; the Persians sit on carpets and lean against the wall. I know you would prefer the Turkish fashion. The Turks drink coffee without either milk or sugar; the Persians drink tea with sugar, though without milk. The Turks wear turbans; the Persians wear high caps of black lamb's-wool.

Not only are their customs different; but their characters. The Turks are grave and the Persians lively. The Turks are silent, the Persians talkative. The Turks are rude, the Persians polite. Now I am sure you like the Persians better than the Turks. But wait a little—the Turks are very proud; the Persians are very deceitful. An old Persian was heard to say, "We all tell lies whenever we can." The Persians are not even ashamed when their falsehoods are found out. When they sell they ask too much; when they make promises they break them. In short, it is impossible to trust a Persian.

The Turks obey Mahomet's laws; they pray five times a day, and drink no wine. But the Persians seldom repeat their prayers, and they do drink wine, though Mahomet has forbidden it. In short, the Persian seems to have no idea of right and wrong. The judges do not give right judgment, but take bribes. The soldiers live by robbing the poor people, for the king pays them no wages, but leaves them to get food as they can; and so the poor people often build their cottages in little nooks in the valleys, where they hope the soldiers will not see them.

THE COUNTRY.—Persia is a high country and a dry country. There are high mountains and wide plains; but there are very few rivers and running brooks, because there is so little rain. However, in some places the Persians have cut canals, and planted willow-trees by their side. Rice will not grow well in such a dry country, but sheep find it very pleasant and wholesome. The hills are covered over with flocks, and the shepherds may be seen leading their sheep and carrying the very young lambs in their arms. This is a sight which reminds us of the good Shepherd: for it is written of Jesus, "He gathered the lambs in his arms."

The sweetest of all flowers grows abundantly in Persia—I mean the rose. The air is filled with its fragrance. The people pluck the rose leaves and dry them in the sun, as we dry hay. How pleasant it must be for children in the spring to play among the heaps of rose-leaves. Once a traveller went to breakfast with a Persian Prince, and he found the company seated upon a heap of rose-leaves, with a carpet spread over it. Afterwards the rose-leaves were sent to the distillers, to be made into rose-water.

Persian cats are beautiful creatures, with fur as soft as silk.

The best melons in the world grow in Persia.

The three chief materials for making clothes are all to be found there in abundance. I mean wool, cotton, and silk. You have heard already of the Persian sheep; so you see there is wool. Cotton trees also abound. Women and children may be been picking the nuts which contain the little pieces of cotton. There are mulberry-trees also to feed the numerous silk worms.

POOR PEOPLE.—The villages where the poor live are miserable places. The houses are of mud, not placed in rows, but straggling, with dirty narrow paths winding between them.

In summer the poor people sleep on the roofs; for the roofs are flat, and covered with earth, with low walls on every side to prevent the sleepers falling off. Here the Persians spread their carpets to lie upon at night.

Winter does not last long in Persia, yet while it lasts it is cold. Then the poor, instead of sleeping on their roofs, sleep in a very curious warm bed. In the middle of each cottage there is a round hole in the floor, where the fire burns. In the evening the fire goes out, but the hot cinders remain. The Persians place over it a low round table, and then throw a large coverlid over the table, and all round about. Under this coverlid the family lie at night, their heads peeping out, and their feet against the warm fire-place underneath. This the Persians call a comfortable bed.

The poor wear dirty and ragged clothes, and the children may be seen crawling about in the dust, and looking like little pigs. Yet in one respect the Persians are very clean; they bathe often. In every village there is a large bath.

The poor people have animals of various kinds—a few sheep, or goats, or cows. In the day one man takes them all out to feed. In the evening he brings them back to the village, and the animals of their own accord go home to their own stables. Each cow and each sheep knows where she will get food and a place to sleep in. The prophet Isaiah said truly, "The ass knoweth his owner, and the ox his master's crib; but Israel doth not know, my people doth not consider."

THE PERSIAN LADIES.—They wrap themselves up in a large dark blue wrapper, and in this dress they walk out where they please. No one who meets them can tell who they are.

And where do these women go? Chiefly to the bath, where they spend much of their time drinking coffee and smoking. There too they try to make themselves handsome by blackening their eyebrows and dyeing their hair. Sometimes the ladies walk to the burial-grounds, and wander about for hours among the graves. When they are at home they employ themselves in making pillau and sherbet. Pillau is made of rice and butter; sherbet is made of juice mixed with water.

The ladies have a sitting-room to themselves. One side of it is all lattice-work, and this makes it cool. At night they spread their carpets on the floor to sleep upon, and in the day they keep them in a lumber-room.

PERSIAN INNS.—They are very uncomfortable places. There are a great many small cells made of mud, built all round a large court. These cells are quite empty, and paved with stone. The only comfortable room is over the door-way of the court, and the first travellers who arrive are sure to settle in the room over the door-way.

Once an English traveller arrived at a Persian inn with his two servants. All three were very ill and in great pain, from having travelled far over burning plains and steep mountains.

But as the room over the door-way was occupied, they were forced to go into a little cold damp cell. As there was no door to the cell, they hung up a rag to keep out the chilling night air, and they placed a pan of coals in the midst. Many Persians came and peeped into the cell; and seeing the sick men looking miserable as they lay on their carpets, the unfeeling creatures laughed at them, and no one would help them or give them anything to eat. The travellers bought some bread and grapes at the bazaar, but these were not fit food for sick men, but it was all they could get. At last a Persian merchant heard of their distress; and he came to see them every day, bringing them warm milk and wholesome food: when they were well enough to be moved, he took them to his own house, and nursed them with the greatest care.

Who was this kind merchant? Not a Mahomedan, but of the religion of the fire worshippers, or Parsees. Was he not like the good Samaritan of whom we read in the New Testament? O that Bahram, the merchant, might know the true God!

PILGRIMS AND BEGGARS.—Very often you may see a large company of Pilgrims some on foot, and some mounted on camels, horses, and asses. They are returning from Mecca, the birth-place of Mahomet. What good have they got by their pilgrimage? None at all. They think they are grown very holy, but they make such an uproar at the inns by quarrelling and fighting when they are travelling home, that no one can bear to be near them.

There is a set of beggars called dervishes. They call themselves very holy, and think people are bound to give money to such holy men. They are so bold that sometimes they refuse to leave a place till some money has been given.

Once a dervish stopped a long while before the house of the English ambassador, and refused to go away. But a plan was thought of to make him go away.

The dervish was sitting in a little niche in the wall. The ambassador ordered his servants to build up bricks to shut the dervish in. The men began to build, yet the dervish would not stir, till the bricks came up as high as his chin: then he began to be frightened, and said he would rather go away.

THE KING OF PERSIA.—He is called King of Kings. What a name for a man! It is the title of God alone. The king sits on a marble throne, and his garments sparkle with jewels of dazzling brightness. The walls of his state-chamber are covered with looking-glasses. One side of the room opens into a court adorned with flowers and fountains. Great part of his time is spent in amusements, such as hunting and shooting, writing verses, and hearing stories. He keeps a man called a story-teller, and he will never hear the same story repeated twice. It gives the man a great deal of trouble to find new stories every day. The king keeps jesters, who make jokes; and he has mimics, who play antics to make him laugh. He dines at eight in the evening from dishes of pure gold. No one is allowed to dine with him; but two of his little boys wait upon him, and his physician stands by to advise him not to eat too much.

Do you think he is happy in all his grandeur? Judge for yourself.

All his golden dishes come up covered and sealed. Why? For fear of poison. There is a chief officer in the kitchen who watches the cook, to see that he puts no poison into the food: and he seals up the dishes before they are taken to the king, in order that the servants may not put in poison as they are carrying them along. In what fear this great king lives! He cannot trust his own servants.

TEHERAN.—This is the royal city. It is built in a barren plain, and is exceedingly hot, as the hills around keep off the air. It is a mean city, for it is chiefly built of mud huts.

The king's palace is called the "Ark," and is a very strong as well as grand place.[5]

Extracted chiefly from Southgate's Travels.

There is no country in the world like China.

How different it is from Persia, where there are so few people; whereas China is crowded with inhabitants!

How different it is from England, where the people are instructed in the Bible, whereas China is full of idols.

China is a heathen country; yet it is not a savage country, for the people are quiet, and orderly, and industrious.

It would be hard for a child to imagine what a great multitude of people there are in China.

If you were to sit by a clock, and if all the Chinese were to pass before you one at a time, and if you were to count one at each tick of the clock, and if you were never to leave off counting day or night—how long do you think it would be before you had counted all the Chinese?

Twelve years. O what a vast number of people there must be in China! In all, there are about three hundred and sixty millions! If all the people in the world were collected together, out of every three one would be a Chinese. How sad it is to think that this immense nation knows not God, nor his glorious Son!

There are too many people in China, for there is not food enough for them all; and many are half-starved.

FOOD.—The poor can get nothing but rice to eat and water to drink; except now and then they mix a little pork or salt fish with their rice. Any sort of meat is thought good; even a hash of rats and snakes, or a mince of earth-worms. Cats and dogs' flesh are considered as nice as pork, and cost as much.

An Englishman was once dining with a Chinaman, and he wished to know what sort of meat was on his plate. But he was not able to speak Chinese. How then could he ask? He thought of a way. Looking first at his plate, and then at the Chinaman, he said, "Ba-a-a," meaning to ask, "Is this mutton?" The Chinaman understood the question, and immediately replied, "Bow-wow," meaning to say, "It is puppy-dog." You will wish to know whether the Englishman went on eating; but I cannot tell you this.

While the poor are in want of food, the rich eat a great deal too much. A Chinese feast in a rich man's house lasts for hours. The servants bring in one course after another, till a stranger wonders when the last course will come. The food is served up in a curious way; not on dishes, but in small basins—for all the meats are swimming in broth. Instead of a knife and fork, each person has a pair of chop-sticks, which are something like knitting-needles; and with these he cleverly fishes up the floating morsels, and pops them into his mouth. There are spoons of china for drinking the broth.

You will be surprised to hear that the Chinese are very fond of eating birds' nests. Do not suppose that they eat magpies' nests, which are made of clay and sticks, or even little nests of moss and clay; the nests they eat are made of a sort of gum. This gum comes out of the bird's mouth, and is shining and transparent, and the nest sticks fast to the rock. These nests are something like our jelly, and must be very nourishing.

The Chinese like nothing cold; they warm all their food, even their wine. For they have wine, not made of grapes, but of rice, and they drink it, not in glasses, but in cups. Tea, however, is the most common drink; for China is the country where tea grows.

The hills are covered with shrubs bearing a white flower, a little like a white rose. They are tea-plants. The leaves are picked; each leaf is rolled up with the finger, and dried on a hot iron plate.

The Chinese do not keep all the tea-leaves; they pack up a great many in boxes, and send them to distant lands. In England and in Russia there is a tea-kettle in every cottage. Some of the Chinese are so very poor that they cannot buy new tea-leaves, but only tea-leaves which ire sold in shops. I do not think in England poor people would buy old tea-leaves. Some very poor Chinese use fern-leaves instead of tea-leaves.

The Chinese do not make tea in the same way that we do. They have no teapot, or milk-jug, or sugar-basin. They put a few tea-leaves in a cup, pour hot water on them, and then put a cover on the cup till the tea is ready. Whenever you pay a visit in China a cup of tea is offered.

APPEARANCE.—The Chinese are not at all like the other natives of Asia. The Turks and Arabs are fine-looking men, but the Chinese are poor-looking creatures. You have seen their pictures on their boxes of tea, for they are fond of drawing pictures of themselves.

Their complexion is rather yellow, but many of the ladies, who keep in doors, are rather fair. They have black hair, small dark eyes, broad faces, flat noses, and high cheek-bones. In general they are short. The men like to be stout; and the rich men are stout: the fatter they are, the more they are admired: but the women like to be slender.

A Chinaman does not take off his cap in company, and he has a good reason for it: his head is close shaven: only a long piece behind is allowed to grow, and this grows down to his heels, and is plaited. He wears a long dark blue gown, with loose hanging sleeves. His shoes are clumsy, turned up at the toes in an ugly manner, and the soles are white. The Chinese have more trouble in whitening their shoes than we have in blacking ours.

A Chinese lady wears a loose gown like a Chinaman's; but she may be known by her head-dress, her baby feet, and her long nails. Her hair is tied up, and decked with artificial flowers; and sometimes a little golden bird, sparkling with jewels, adorns her forehead. Her feet are no bigger than those of a child of five years old; because, when she was five, they were cruelly bound up to prevent them from growing. She suffered much pain all her childhood, and now she trips about as if she were walking on tiptoes. A little push would throw her down. As she walks she moves from side to side like a ship in the water, for she cannot walk firmly with such small feet. The Chinese are so foolish as to admire these small feet, and to call them the "golden lilies". As for her finger-nails, they are seldom seen, for a Chinese lady hides her hands in her long sleeves; but the nails on the left hand are very long, and are like bird's claws. The nails on the right hand are not so long, in order that the lady may be able to tinkle on her music, to embroider, and to weave silk.

The gentlemen are proud of having one long nail on the little finger, to show that they do not labor like the poor, for if they did, the nail would break. Men in China wear necklaces and use fans.

What foolish customs I have described. Surely you will not think the Chinese a wise people, though very clever, as you will soon find.

Men and women dress in black, or in dark colors, such as blue and purple; the women sometimes dress in pink or green. Great people dress in red, and the royal family in yellow. When you see a person all in white, you may know he is in mourning. A son dresses in white for three years after he has lost one of his parents.

HOUSES.—See that lantern hanging over the gate. The light is rather dim, because the sides are made of silk instead of glass. What is written upon the lantern? The master's name. The gateway leads into a court into which many rooms open. There are not doors to all the rooms; to some there are only curtains. Curtains are used instead of doors in many hot countries, because of their coolness; but the furniture of the Chinese rooms is quite different from the furniture of Turkish and Persian rooms. The Chinese sit on chairs as we do, and have high tables like ours: and they sleep on bedsteads, yet their beds are not like ours, for instead of a mattrass there is nothing but a mat.

Instead of pictures, the Chinese adorn their rooms with painted lanterns, and with pieces of white satin, on which sentences are written: they have also book-cases and china jars. But they have no fire-places, for they never need a fire to keep themselves warm: the sun shining in at the south windows makes the rooms tolerably warm in winter; and in summer the weather is very hot. The Chinese in winter put on one coat over the other till they feel warm enough. In the north of China it is so cold in winter that the place where the bed stands (which is a recess in the wall) is heated by a furnace underneath, and the whole family sit there all day crowded together.

The Chinese houses have not so many stories as ours; in the towns there is one floor above the ground floor, but in the country there are no rooms up stairs.

It would amuse you to see a Chinese country house. There is not one large house, but a number of small buildings like summer-houses, and long galleries running from one to another. One of these summer-houses is in the middle of a pond, with a bridge leading to it. In the pond there are gold and silver fish; for these beautiful fishes often kept in glass bowls in England, came first from China. By the sides of the garden walls large cages are placed; in one may be seen some gold and silver pheasants, in another a splendid peacock; in another a gentle stork, and in another an elegant little deer. There is often a grove of mulberry-trees in the garden, and in the midst of the grove houses made of bamboo, for rearing silk-worms. It is the delight of the ladies to feed these curious worms. None but very quiet people are fit to take care of them, for a loud noise would kill them. Gold and silver fish also cannot bear much noise.

In every large house in China there is a room called the Hall of Ancestors. There the family worship their dead parents and grand-parents, and great-grand-parents, and those who lived still further back. There are no images to be seen in the Hall of Ancestors, but there are tablets with names written upon them. The family bow down before the tablets, and burn incense and gold paper! What a foolish service! What good can incense and paper do to the dead? And what good can the dead do to their children? How is it that such clever people as the Chinese are so foolish?

RELIGION.—You have heard already that the Chinese worship the dead.

Who taught them this worship?

It was a man named Confucius, who lived a long while ago. This Confucius was a very wise man. From his childhood he was very fond of sitting alone thinking, instead of playing with other children. When he was fourteen he began to read some old books that had been written not long after the time of Noah. In these books he found very many wise sentences, such as Noah may have taught his children. The Chinese had left off reading these wise books, and were growing more and more foolish.[6] Confucius, when he was grown up, tried to persuade his countrymen to attend to the old books. There were a few men who became his scholars, and who followed him about from place to place. They might be seen sitting under a tree, listening to the words of Confucius.

Confucius was a very tall man with a long black beard and a very high forehead.

Had he known the true God, how much good he might have done to the Chinese; but as it was he only tried to make them happy in this world. He himself confessed that he knew nothing about the other world. He gave very good advice about respect due to parents; but he gave very bad advice about worship due to them after they were dead.

Was he a good man? Not truly good; for he did not love God; neither did he act right: for he was very unkind to his wife, and quite cast her off. Yet he used to talk of going to other countries to teach the people. It would have been a happy thing for him, if he had gone as far as Babylon; for a truly wise man lived there, even Daniel the prophet. From him he might have learned about the promised Saviour, and life everlasting. But Confucius never left China.

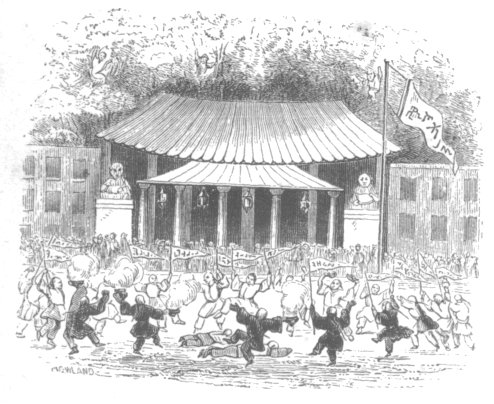

He was ill-treated by many of the rich and great, and he was so poor that rice was generally his only food. When he was dying he felt very unhappy, as well he might, when he knew not where he was going. He said to his followers just before his death, "The kings refuse to follow my advice; and since I am of no use on earth, it is best that I should leave it." As soon as he was dead, people began to respect him highly, and even to worship him. At this day, though Confucius died more than two thousand years ago, there is a temple to his honor in every large city, and numbers of beasts are offered up to him in sacrifice. There are thousands of people descended from him, and they are treated with great honor as the children of Confucius, and one of them is called kong or duke.