SIR FRANCIS DRAKE.

Title: A Short History of the United States for School Use

Author: Edward Channing

Release date: May 1, 2004 [eBook #12423]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Keren Vergon, Charlie Kirschner and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

[Illustration: ABRAHAM LINCOLN.]

The aim of this little book is to tell in a simple and concise form the story of the founding and development of the United States. The study of the history of one's own country is a serious matter, and should be entered upon by the text-book writer, by the teacher, and by the pupil in a serious spirit, even to a greater extent than the study of language or of arithmetic. No effort has been made, therefore, to make out of this text-book a story book. It is a text-book pure and simple, and should be used as a text-book, to be studied diligently by the pupil and expounded carefully by the teacher.

Most of the pupils who use this book will never have another opportunity to study the history and institutions of their own country. It is highly desirable that they should use their time in studying the real history of the United States and not in learning by heart a mass of anecdotes,--often of very slight importance, and more often based on very insecure foundations. The author of this text-book, therefore, has boldly ventured to omit most of the traditional matter which is usually supposed to give life to a text-book and to inspire a "love of history,"--which too often means only a love of being amused. For instance, descriptions of the formation of the Constitution and of the struggle over the extension of slavery here occupy the space usually given to the adventures of Captain John Smith and to accounts of the institutions of the Red Men. The small number of pages available for the period before 1760 has necessitated the omission of "pictures of colonial life," which cannot be briefly and at the same time accurately described. These and similar matters can easily be studied by the pupils in their topical work in such books as Higginson's Young Folks' History, Eggleston's United States and its People, and McMaster's School History. References to these books and to a limited number of other works have been given in the margins of this text-book. These citations also mention a few of the more accessible sources, which should be used solely for purposes of illustration.

It is the custom in many schools to spread the study of American history over two years, and to devote the first year to a detailed study of the period before 1760. This is a very bad arrangement. In the first place, it gives an undue emphasis to the colonial period; in the second place, as many pupils never return to school, they never have an opportunity to study the later period at all; in the third place, it prevents those pupils who complete this study from gaining an intelligent view of the development of the American people. And, finally, most of the time the second year is spent in the study of the Revolutionary War and of the War for the Union. A better way would be to go over the whole book the first year with some parallel reading, and the second year to review the book and study with greater care important episodes, as the making of the Constitution, the struggle for freedom in the territories, and the War for the Union. Attention may also be given the second year to a study of industrial history since 1790 and to the elements of civil government. It is the author's earnest hope that teachers will regard the early chapters as introductory.

Miss Annie Bliss Chapman, for many years a successful teacher of history in grammar schools, has kindly provided a limited number of suggestive questions, and has also made many excellent suggestions to teachers. These are all appended to the several divisions of the work. The author has added a few questions and a few suggestions of his own. He has also altered some of Miss Chapman's questions. Whatever there is commendable in this apparatus should be credited to Miss Chapman. Acknowledgments are also due to Miss Beulah Marie Dix for very many admirable suggestions as to language and form. The author will cordially welcome criticisms and suggestions from any one, especially from teachers, and will be very glad to receive notice of any errors.

CAMBRIDGE,

March 29, 1900.

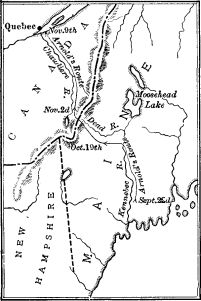

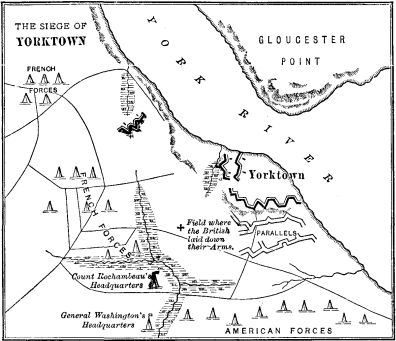

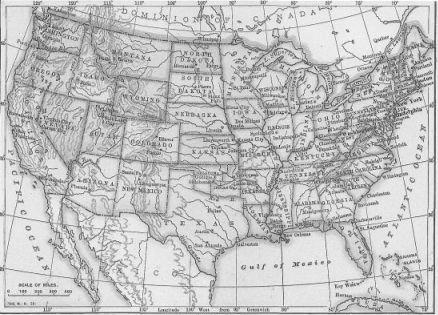

UNITED STATES, SHOWING FORMS OF LAND.

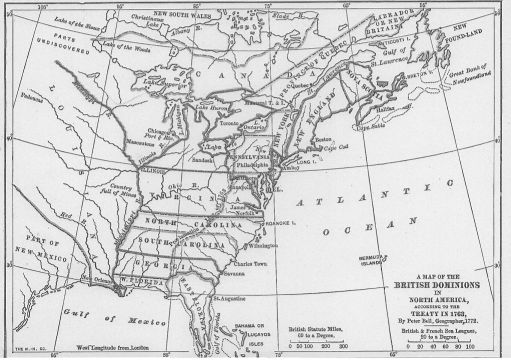

BRITISH DOMINIONS IN NORTH AMERICA.

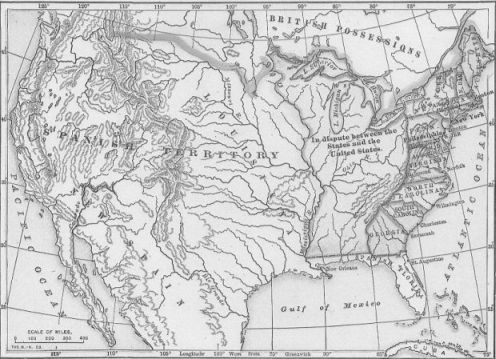

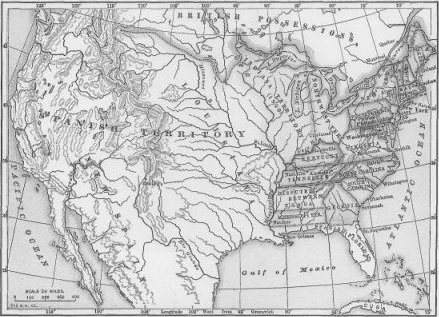

UNITED STATES IN 1783.

CLAIMS AND CESSIONS.

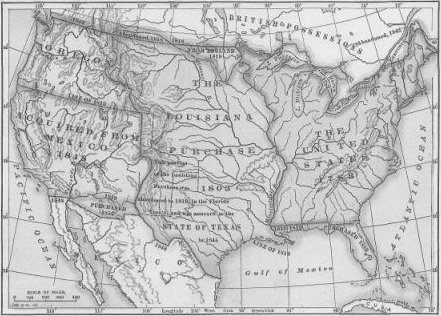

TERRITORIAL ACQUISITIONS.

UNITED STATES IN 1800.

UNITED STATES IN 1803.

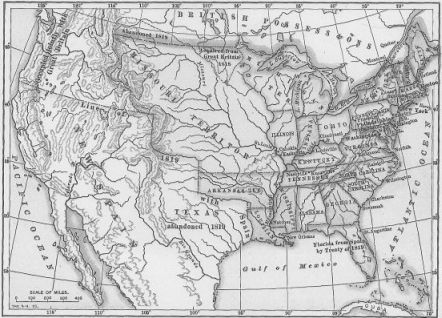

UNITED STATES IN 1819.

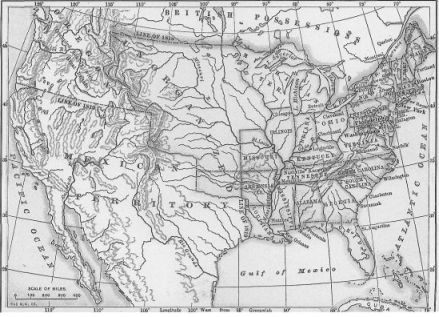

UNITED STATES IN 1830.

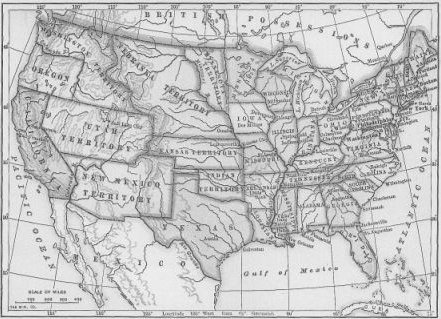

UNITED STATES IN 1850.

UNITED STATES IN 1860.

SLAVERY AND SECESSION.

UNITED STATES IN 1900.

DEPENDENCIES OF THE UNITED STATES.

THE WORLD, ETC..

Table of Dates

1815-1824. Era of Good Feeling.

1819. The Florida Treaty.

1820. Missouri Compromise.

1823. The Monroe Doctrine.

1825. The Erie Canal.

1828. Election of Jackson.

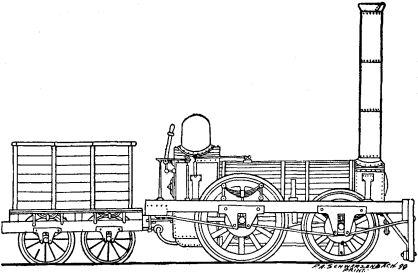

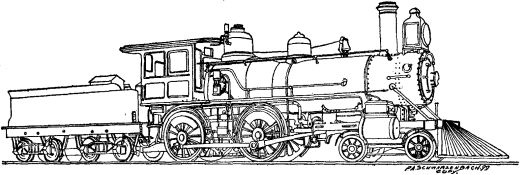

1830. The Locomotive.

1832. The Nullification Episode.

1840. Election of William H. Harrison.

1844. The Electric Telegraph.

1845. The Horse Reaper.

1845. Annexation of Texas.

1846. The Oregon Treaty.

1846-1848. The Mexican War (Acquisition of California, New Mexico,

etc.)

1849. California (Discovery of Gold).

1850. Compromise of 1850.

1854. Kansas-Nebraska Act.

1857. The Dred Scott Case.

1861-1865. The War for the Union.

1863. Emancipation Proclamation, Vicksburg, and Gettysburg.

1867. Purchase of Alaska.

1867. Reconstruction Acts.

1868. Impeachment of Johnson.

1876. The Electoral Commission.

1881-1883. Civil Service Reform.

1890. Sherman Silver Law (Repealed, 1893).

1898. The War with Spain.

The lists of "Books for Study and Reading" contain such titles only as are suited to the pupil's needs. The teacher will find abundant references in Channing's Students' History of the United States (N.Y., Macmillan). The larger work also contains the reasons for many statements which are here given as facts without qualification. Reference to the Students' History is made easy by the fact that the divisions or parts (here marked by Roman numerals) cover the same periods in time as the chapters of the larger work. On the margins of the present volume will be found specific references to three text-books radically unlike this text-book either in proportion or in point of view. There are also references to easily accessible sources and to a few of the larger works. It is not suggested that any one pupil, or even one class, shall study or read all of these references. But every pupil may well read some of them under each division. They are also suited to topical work. Under the head of "Home Readings" great care has been taken to mention such books only as are likely to be found interesting.

The books most frequently cited in the margins are Higginson's Young Folks' History (N.Y., Longmans), cited as "Higginson"; Eggleston's United States and its People (N.Y., Appleton), cited as "Eggleston", McMaster's School History of the United States (N.Y., American Book Co.), cited as "McMaster"; Higginson's Book of American Explorers (N.Y., Longmans), cited as "Explorers"; Lodge and Roosevelt, Hero Tales from American History, cited as "Hero Tales"; and Hart's Source-Book of American History (N.Y., Macmillan), cited as "Source-Book." Books containing sources are further indicated by an asterisk.

References.--Parkman's Pioneers of France (edition of 1887 or a later edition); Irving's Columbus (abridged edition).

Home Readings.--Higginson's Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic; Mackie's With the Admiral of the Ocean Sea (Columbus); Lummis's Spanish Pioneers; King's De Soto in the Land of Florida; Wright's Children's Stories in American History; Barnes's Drake and his Yeomen.

Leif Ericson.

1. Leif Ericson discovers America, 1000.--In our early childhood many of us learned to repeat the lines:--

Columbus sailed the ocean blue

In fourteen hundred, ninety-two.

Leif discovers America, 1000. Higginson, 25-30; American History Leaflets, No. 3.

We thought that he was the first European to visit America. But nearly five hundred years before his time Leif Ericson had discovered the New World. He was a Northman and the son of Eric the Red. Eric had already founded a colony in Greenland, and Leif sailed from Norway to make him a visit. This was in the year 1000. Day after day Leif and his men were tossed about on the sea until they reached an unknown land where they found many grape-vines. They called it Vinland or Wineland. They Then sailed northward and reached Greenland in safety. Precisely where Vinland was is not known. But it certainly was part of North America. Leif Ericson, the Northman, was therefore the real discoverer of America.

[Illustration: EUROPE, ICELAND, GREENLAND, AND NORTH AMERICA.]

Marco Polo, Cathay, and Cipango.

2. Early European Travelers.--The people of Europe knew more of the lands of Asia than they knew of Vinland. For hundreds of years missionaries, traders, and travelers visited the Far East. They brought back to Europe silks and spices, and ornaments of gold and of silver. They told marvelous tales of rich lands and great princes. One of these travelers was a Venetian named Marco Polo. He told of Cathay or China and of Cipango or Japan. This last country was an island. Its king was so rich that even the floors of his palaces were of pure gold. Suddenly the Turks conquered the lands between Europe and the golden East. They put an end to this trading and traveling. New ways to India, China, and Japan must be found.

Portuguese seamen.

3. Early Portuguese Sailors.--One way to the East seemed to be around the southern end of Africa--if it should turn out that there was a southern end to that Dark Continent. In 1487 Portuguese seamen sailed around the southern end of Africa and, returning home, called that point the Cape of Storms. But the King of Portugal thought that now there was good hope of reaching India by sea. So he changed the name to Cape of Good Hope. Ten years later a brave Portuguese sailor, Vasco da Gama, actually reached India by the Cape of Good Hope, and returned safely to Portugal (1497).

Columbus and his beliefs. Higginson, 31-35; Eggleston, 1-3; American History Leaflets, No. 1.

4. Columbus.--Meantime Christopher Columbus, an Italian, had returned from an even more startling voyage. From what he had read, and from what other men had told him, he had come to believe that the earth was round. If this were really true, Cipango and Cathay were west of Europe as well as east of Europe. Columbus also believed that the earth was very much smaller than it really is, and that Cipango was only three thousand miles west of Spain. For a time people laughed at the idea of sailing westward to Cipango and Cathay. But at length Columbus secured enough money to fit out a little fleet.

Columbus reaches America, 1492. Higginson, 35-37; Eggleston, 3-5.

5. The Voyage, 1492.--Columbus left Spain in August, 1492, and, refitting at the Canaries, sailed westward into the Sea of Darkness. At ten o'clock in the evening of October 20, 1492, looking out into the night, he saw a light in the distance. The fleet was soon stopped. When day broke, there, sure enough, was land. A boat was lowered, and Columbus, going ashore, took possession of the new land for Ferdinand and Isabella, King and Queen of Aragon and Castile. The natives came to see the discoverers. They were reddish in color and interested Columbus--for were they not inhabitants of the Far East? So he called them Indians.

[Illustration: SHIPS, SEA-MONSTERS, AND INDIANS. From an early Spanish book on America.]

The Indians, Higginson, 13-24; Eggleston,

71-76.

Columbus discovers Cuba.

6. The Indians and the Indies.--These Indians were not at all like those wonderful people of Cathay and Cipango whom Marco Polo had described. Instead of wearing clothes of silk and of gold embroidered satin, these people wore no clothes of any kind. But it was plain enough that the island they had found was not Cipango. It was probably some island off the coast of Cipango, so on Columbus sailed and discovered Cuba. He was certain that Cuba was a part of the mainland of Asia, for the Indians kept saying "Cubanaquan." Columbus thought that this was their way of pronouncing Kublai Khan--the name of a mighty eastern ruler. So he sent two messengers with a letter to that powerful monarch. Returning to Spain, Columbus was welcomed as a great admiral. He made three other voyages to America. But he never came within sight of the mainland of the United States.

John Cabot visits North America, 1497. Higginson, 40-42; Eggleston, 8-10; American History Leaflets, No. 9.

7. John Cabot, 1497.--While Columbus explored the West Indies, another Italian sailed across the Sea of Darkness farther north. His name was John Cabot, and he sailed with a license from Henry VII of England, the first of the Tudor kings. Setting boldly forth from Bristol, England, he crossed the North Atlantic and reached the coast of America north of Nova Scotia. Like Columbus, he thought that he had found the country of the Grand Khan. Upon his discovery English kings based their claim to the right to colonize North America.

Americus Vespucius, his voyages and books.

Higginson, 37-38; Eggleston, 7-8.

The New World named America.

8. The Naming of America.--Many other explorers also visited the new-found lands. Among these was an Italian named Americus Vespucius. Precisely where he went is not clear. But it is clear that he wrote accounts of his voyages, which were printed and read by many persons. In these accounts he said that what we call South America was not a part of Asia. So he named it the New World. Columbus all the time was declaring that the lands he had found were a part of Asia. It was natural, therefore, that people in thinking of the New World should think of Americus Vespucius. Before long some one even suggested that the New World should be named America in his honor. This was done, and when it became certain that the other lands were not parts of Asia, the name America was given to them also until the whole continent came to be called America.

[Illustration: AMERICUS VESPUCIUS.]

Balboa sees the Pacific, 1513.

Magellan's great voyage, 1520. Eggleston, 10-11.

9. Balboa and Magellan, 1513, 1520.--Balboa was a Spaniard who came to San Domingo to seek his fortune. He became a pauper and fled away from those to whom he owed money. After long wanderings he found himself on a high mountain in the center of the Isthmus of Panama. To the southward sparkled the waters of a new sea. He called it the South Sea. Wading into it waist deep, he waved his sword in the air and took possession of it for his royal master, the King of Spain. This was in 1513. Seven years later, in 1520, Magellan, a Portuguese seaman in the service of the Spanish king, sailed through the Straits of Magellan and entered the same great ocean, which he called the Pacific. Thence northward and westward he sailed day after day, week after week, and month after month, until he reached the Philippine Islands. The natives killed Magellan. But one of his vessels found her way back to Spain around the Cape of Good Hope.

Indian traditions.

10. Stories of Golden Lands.--Wherever the Spaniards went, the Indians always told them stories of golden lands somewhere else. The Bahama Indians, for instance, told their cruel Spanish masters of a wonderful land toward the north. Not only was there gold in that land; there was also a fountain whose waters restored youth and vigor to the drinker. Among the fierce Spanish soldiers was Ponce de Leon (Pon'tha da la-on'). He determined to see for himself if these stories were true.

De Leon visits Florida, 1513. Higginson,

42.

De Leon's death.

11. Discovery of Florida, 1513.--In the same year that Balboa discovered the Pacific Ocean, Ponce de Leon sailed northward and westward from the Bahamas. On Easter Sunday, 1513, he anchored off the shores of a new land. The Spanish name for Easter was La Pascua de los Flores. So De Leon called the new land Florida. For the Spaniards were a very religious people and usually named their lands and settlements from saints or religious events. De Leon then sailed around the southern end of Florida and back to the West Indies. In 1521 he again visited Florida, was wounded by an Indian arrow, and returned home to die.

Discovery of the Mississippi.

Conquest of Mexico.

12. Spanish Voyages and Conquests.--Spanish sailors and conquerors now appeared in quick succession on the northern and western shores of the Gulf of Mexico. One of them discovered the mouth of the Mississippi. Others of them stole Indians and carried them to the islands to work as slaves. The most famous of them all was Cortez. In 1519 he conquered Mexico after a thrilling campaign and found there great store of gold and silver. This discovery led to more expeditions and to the exploration of the southern half of the United States.

Coronado sets out from Mexico, 1540.

The pueblo Indians. Source Book, 6.

13. Coronado in the Southwest, 1540-42.--In 1540 Coronado set out from the Spanish towns on the Gulf of California to seek for more gold and silver. For seventy-three days he journeyed northward until he came to the pueblos (pweb'-lo) of the Southwest. These pueblos were huge buildings of stone and sun-dried clay. Some of them were large enough to shelter three hundred Indian families. Pueblos are still to be seen in Arizona and New Mexico, and the Indians living in them even to this day tell stories of Coronado's coming and of his cruelty. There was hardly any gold and silver in these "cities," so a great grief fell upon Coronado and his comrades.

[Illustration: By permission of the Bureau of Ethnology. THE PUEBLO OF ZUÑI (FROM A PHOTOGRAPH).]

Coronado finds the Great Plains.

14. The Great Plains.--Soon, however, a new hope came to the Spaniards, for an Indian told them that far away in the north there really was a golden land. Onward rode Coronado and a body of picked men. They crossed vast plains where there were no mountains to guide them. For more than a thousand miles they rode on until they reached eastern Kansas. Everywhere they found great herds of buffaloes, or wild cows, as they called them. They also met the Indians of the Plains. Unlike the Indians of the pueblos, these Indians lived in tents made of buffalo hides stretched upon poles. Everywhere there were plains, buffaloes, and Indians. Nowhere was there gold or silver. Broken hearted, Coronado and his men rode southward to their old homes in Mexico.

De Soto in Florida, 1539. Explorers,

119-138.

De Soto crosses the Mississippi.

15. De Soto in the Southeast, 1539-43.--In 1539 a Spanish army landed at Tampa Bay, on the western coast of Florida. The leader of this army was De Soto, one of the conquerors of Peru. He "was very fond of the sport of killing Indians" and was also greedy for gold and silver. From Tampa he marched northward to South Carolina and then marched southwestward to Mobile Bay. There he had a dreadful time; for the Indians burned his camp and stores and killed many of his men. From Mobile he wandered northwestward until he came to a great river. It was the Mississippi, and was so wide that a man standing on one bank could not see a man standing on the opposite bank. Some of De Soto's men penetrated westward nearly to the line of Coronado's march. But the two bands did not meet. De Soto died and was buried in the Mississippi. Those of his men who still lived built a few boats and managed to reach the Spanish settlements in Mexico.

Other Spanish explorers.

Attempts at settlement.

16. Other Spanish Expeditions.--Many other Spanish explorers visited the shores of the United States before 1550. Some sailed along the Pacific coast; others sailed along the Atlantic coast. The Spaniards also made several attempts to found settlements both on the northern shore of the Gulf of Mexico and on Chesapeake Bay. But all these early attempts ended in failure. In 1550 there were no Spaniards on the continent within the present limits of the United States, except possibly a few traders and missionaries in the Southwest.

Verrazano's voyages, 1524. Higginson, 44-45;

Explorers, 60-69.

Cartier in the St. Lawrence, 1534-36. Explorers 99-117.

17. Early French Voyages, 1524-36.--The first French expedition to America was led by an Italian named Verrazano (Ver-rä-tsä'-no), but he sailed in the service of Francis I, King of France. He made his voyage in 1524 and sailed along the coast from the Cape Fear River to Nova Scotia. He entered New York harbor and spent two weeks in Newport harbor. He reported that the country was "as pleasant as it is possible to conceive." The next French expedition was led by a Frenchman named Cartier (Kar'-tya'). In 1534 he visited the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In 1535 he sailed up the St. Lawrence River to Montreal. But before he could get out of the river again the ice formed about his ships. He and his crew had to pass the winter there. They suffered terribly, and twenty-four of them perished of cold and sickness. In the spring of 1536 the survivors returned to France.

Ribault explores the Carolina coasts, 1562.

French colonists in Carolina. Explorers, 149-156.

18. The French in Carolina, 1562.--The French next explored the shores of the Carolinas. Ribault (Re'-bo') was the name of their commander. Sailing southward from Carolina, he discovered a beautiful river and called it the River of May. But we know it by its Spanish name of St. Johns. He left a few men on the Carolina coast and returned to France. A year or more these men remained. Then wearying of their life in the wilderness, they built a crazy boat with sails of shirts and sheets and steered for France. Soon their water gave out and then their food. Finally, almost dead, they were rescued by an English ship.

French colonists in Florida.

19. The French in Florida, 1564-65.--While these Frenchmen were slowly drifting across the Atlantic, a great French expedition was sailing to Carolina. Finding Ribault's men gone, the new colony was planted on the banks of the River of May. Soon the settlers ate up all the food they had brought with them. Then they bought food from the Indians, giving them toys and old clothes in exchange. Some of the colonists rebelled. They seized a vessel and sailed away to plunder the Spaniards in the West Indies. They told the Spaniards of the colony on the River of May, and the Spaniards resolved to destroy it.

Spaniards and Frenchmen.

End of the French settlement, 1565. Explorers, 159-166.

20. The Spaniards in Florida, 1565.--For this purpose the Spaniards sent out an expedition under Menendez (Ma-nen'-deth). He sailed to the River of May and found Ribault there with a French fleet. So he turned southward, and going ashore founded St. Augustine. Ribault followed, but a terrible storm drove his whole fleet ashore south of St. Augustine. Menendez then marched over land to the French colony. He surprised the colonists and killed nearly all of them. Then going back to St. Augustine, he found Ribault and his shipwrecked sailors and killed nearly all of them. In this way ended the French attempts to found a colony in Carolina and Florida. But St. Augustine remained, and is to-day the oldest town on the mainland of the United States.

Hawkins's voyages, 1562-67.

21. Sir John Hawkins.--For many years after Cabot's voyage Englishmen were too busy at home to pay much attention to distant expeditions. But in Queen Elizabeth's time English seamen began to sail to America. The first of them to win a place in history was John Hawkins. He carried cargoes of negro slaves from Africa to the West Indies and sold them to the Spanish planters. On his third voyage he was basely attacked by the Spaniards and lost four of his five ships. Returning home, he became one of the leading men of Elizabeth's little navy and fought most gallantly for his country.

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE.

Drake on the California coast, 1577-78. Source-Book, 9.

22. Sir Francis Drake.--A greater and a more famous man was Hawkins's cousin, Francis Drake. He had been with Hawkins on his third voyage and had come to hate Spaniards most vigorously. In 1577 he made a famous voyage round the world. Steering through the Straits of Magellan, he plundered the Spanish towns on the western coasts of South America. At one place his sailors went on shore and found a man sound asleep. Near him were four bars of silver. "We took the silver and left the man," wrote the old historian of the voyage. Drake also captured vessels loaded with gold and silver and pearls. Sailing northward, he repaired his ship, the Pelican, on the coast of California, and returned home by the way of the Cape of Good Hope.

Ralegh and his colonies. Eggleston, 13-17; Explorers, 177-189.

23. Sir Walter Ralegh.--Still another famous Englishman of Elizabeth's time was Walter Ralegh. He never saw the coasts of the United States, but his name is rightly connected with our history, because he tried again and again to found colonies on our shores. In 1584 he sent Amadas and Barlowe to explore the Atlantic seashore of North America. Their reports were so favorable that he sent a strong colony to settle on Roanoke Island in Virginia, as he named that region. But the settlers soon became unhappy because they found no gold. Then, too, their food began to fail, and Drake, happening along, took them back to England.

Ralegh's last attempt, 1587. Explorers, 189-200.

24. The "Lost Colony," 1587.--Ralegh made still one more attempt to found a colony in Virginia. But the fate of this colony was most dreadful. For the settlers entirely disappeared,--men, women, and children. Among the lost was little Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America. No one really knows what became of these people. But the Indians told the later settlers of Jamestown that they had been killed by the savages.

Ruin of Spain's sea-power. English History for Americans, 131-135.

25. Destruction of the Spanish Armada, 1588.--This activity of the English in America was very distressing to the King of Spain. For he claimed all America for himself and did not wish Englishmen to go thither. He determined to conquer England and thus put an end to these English voyages. But Hawkins, Drake, Ralegh, and the men behind the English guns were too strong even for the Invincible Armada. Spain's sea-power never recovered from this terrible blow. Englishmen could now found colonies with slight fear of the Spaniards. When the Spanish king learned of the settlement of Jamestown, he ordered an expedition to go from St. Augustine to destroy the English colony. But the Spaniards never got farther than the mouth of the James River. For when they reached that point, they thought they saw the masts and spars of an English ship. They at once turned about and sailed back to Florida as fast as they could go.

QUESTIONS AND TOPICS

CHAPTER 1

§§ 1-3.--a. To how much honor are the Northmen entitled as the discoverers of America?

b. Draw from memory a map showing the relative positions of Norway, Iceland, Greenland, and North America.

c. What portions of the world were known to Europeans in 1490? Explain by drawing a map.

§§ 4-6.--a. State Columbus's beliefs about the shape and size of the earth.

b. What land did Columbus think that he had reached?

c. What is meant by the statement that "he took possession" of the new land?

d. Describe the appearance of the Indians, their food, and their weapons.

§§ 7-9.--a. What other Italians sailed across the Atlantic before 1500? Why was Cabot's voyage important?

b. Why was the New World called America and not Columbia?

c. Describe the discovery of the Pacific Ocean. Why was this discovery of importance?

CHAPTER 2

§§ 10-12.--a. What was the chief wish of the Spanish explorers?

b. How did they treat the Indians?

§§ 13-16.--a. Describe a pueblo. What do the existing pueblos teach us about the Indians of Coronado's time?

b. Describe Coronado's march.

c. What other band of Spaniards nearly approached Coronado's men? Describe their march.

d. What other places were explored by the Spaniards?

§§ 17-20.--a. Why did Verrazano explore the northeastern coasts?

b. Describe Cartier's experiences in the St. Lawrence.

c. Describe the French expeditions to Carolina and Florida.

d. What reason had the Spaniards for attacking the French?

CHAPTER 3

§§ 21, 22.--a. Look up something about the early voyages of Francis Drake.

b. Compare Drake's route around the world with that of Magellan.

§§ 23-25.--a. Explain carefully Ralegh's connection with our history.

b. Was the territory Ralegh named Virginia just what is now the state of Virginia?

c. What is sea-power?

d. What effect did the defeat of Spain have upon our history?

GENERAL QUESTIONS

a. Draw upon an Outline Map the routes of all the explorers mentioned. Place names and dates in their proper places.

b. Arrange a table of the various explorers as follows, stating in two or three words what each accomplished:--

DATE. SPANISH. FRENCH. ENGLISH. 1492 Columbus 1497 Cabot.

TOPICS FOR SPECIAL WORK

a. Columbus's first voyage, Irving (abridged edition).

b. Coronado's expedition, Lummis's Spanish Pioneers.

c. Verrazano and Cartier, Higginson's Explorers.

d. The "Lost Colony," Higginson's Explorers.

e. The England of Elizabeth (a study of any small history of England will suffice for this topic).

SUGGESTIONS TO THE TEACHER

The teacher is recommended to study sources in preparing her work, making selections where possible, for the pupil's use. Some knowledge of European history (English especially) is essential for understanding our early history, and definite work of this nature on the teacher's part, at least, is earnestly advised.

Encourage outside reading by assigning subjects for individual preparation, the results to be given to the class. Let the children keep note books for entering the important points thus given.

Map study and map drawing should be constant, but demand correct relations rather than finished drawings. Geographical environment should be emphasized as well as the influence of natural resources and productions in developing the country and in determining its history.

In laying out the work on this period the teacher should remember that this part is in the nature of an introduction.

References.--Fiske's United States for Schools, 59-133; Eggleston's United States and its People, 91-113 (for colonial life); Parkman's Pioneers (for French colonies); Bradford's Plymouth Plantation (extracts in "American History Leaflets," No. 29).

Home Readings.--Drake's Making of New England; Drake's Making of Virginia and the Middle States; Eggleston's Pocahontas and Powhatan; Dix's Soldier Rigdale (Pilgrim children); Irving's Knickerbocker History; Webster's Plymouth Oration; Longfellow's Myles Standish; Moore's Pilgrims and Puritans.

Settlement of Acadia, 1604.

Port Royal.

26. The French in Acadia.--For nearly forty years after the destruction of the colony on the River of May, Frenchmen were too busy fighting one another at home to send any more colonists to America. At length, in 1604, a few Frenchmen settled on an island in the St. Croix River. But the place was so cold and windy that after a few months they crossed the Bay of Fundy and founded the town of Port Royal. The country they called Acadia.

Champlain at Plymouth.

Quebec founded, 1608.

Champlain on Lake Champlain, 1609.

He attacks the Iroquois. Explorers, 269-278.

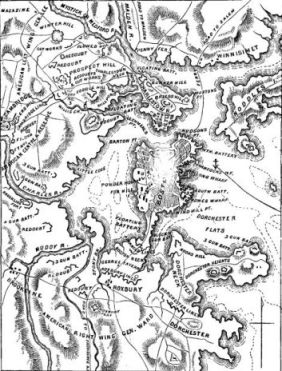

27. Champlain and his Work.--The most famous of these colonists was Champlain. He sailed along the coast southward and westward as far as Plymouth. As he passed by the mouth of Boston harbor, a mist hung low over the water, and he did not see the entrance. Had it been clear he would have discovered Boston harbor and Charles River, and French colonists might have settled there. In 1608 Champlain built a trading-post at Quebec and lived there for many years as governor or chief trader. He soon joined the St. Lawrence Indians in their war parties and explored large portions of the interior. In 1609 he went with the Indians to a beautiful lake. Far away to the east were mountains covered with snow. To the south were other mountains, but with no snow on their tops. To the lake the explorer gave his own name, and we still call it in his honor, Lake Champlain. While there, he drove away with his firearms a body of Iroquois Indians. A few years later he went with another war party to western New York and again attacked the Iroquois.

French missionaries and traders.

They visit Lake Superior and Lake Michigan.

28. The French on the Great Lakes.--Champlain was the first of many French discoverers. Some of these were missionaries who left home and friends to bring the blessings of Christianity to the Red Men of the western world. Others were fur-traders, while still others were men who came to the wilderness in search of excitement. These French discoverers found Lake Superior and Lake Michigan; they even reached the headwaters of the Wisconsin River--a branch of the Mississippi.

The Jesuits and their work.

29. The French Missionaries.--The most active of the French missionaries were the Jesuits. built stations on the shores of the Great Lakes. They made long expeditions to unknown regions. Some of them were killed by those whom they tried to convert to Christianity. Others were robbed and left to starve. Others still were tortured and cruelly abused. But the prospect of starvation, torture, and death only made them more eager to carry on their great work.

[Illustration: CHAMPLAIN'S ATTACK ON AN IROQUOIS FORT.]

The League of the Iroquois.

Their hatred of the French. Its importance.

The missionaries and the Iroquois.

30. The Iroquois.--The strongest of all the Indian tribes were the nations who formed the League of the Iroquois. Ever since Champlain fired upon them they hated the sight of a Frenchman. On the other hand, they looked upon the Dutch and the English as their friends. French missionaries tried to convert them to Christianity as they had converted the St. Lawrence Indians. But the Iroquois saw in this only another attempt at French conquest. So they hung red-hot stones about the missionaries' necks, or they burned them to death, or they cut them to pieces while yet living. For a century and a half the Iroquois stood between the Dutch and English settlers and their common enemies in Canada. Few events, in American history, therefore, have had such great consequences as Champlain's unprovoked attacks upon the Iroquois.

New conditions of living in England.

The Virginia Company.

31. The Virginia Company, 1606.--English people were now beginning to think in earnest of founding colonies. It was getting harder and harder to earn one's living in England, and it was very difficult to invest one's money in any useful way. It followed, from this, that there were many men who were glad to become colonists, and many persons who were glad to provide money to pay for founding colonies. In 1606 the Virginia Company was formed and colonization began on a large scale.

The Virginia colonists at Jamestown, 1607.

Higginson, 52, 110-117; Eggleston, 19-28;

Explorers 231-269.

Sickness and death.

32. Founding of Jamestown, 1607. The first colonists sailed for Virginia in December, 1606. They were months on the way and suffered terrible hardships. At last they reached Chesapeake Bay and James River and settled on a peninsula on the James, about thirty miles from its mouth. Across the little isthmus which connected this peninsula with the mainland they built a strong fence, or stockade, to keep the Indians away from their huts. Their settlement they named Jamestown. The early colonists of Virginia were not very well fitted for such a work. Some of them were gentlemen who had never labored with their hands; others were poor, idle fellows whose only wish was to do nothing whatever. There were a few energetic men among them as Ratcliffe, Archer, and Smith. But these spent most of their time in exploring the bay and the rivers, in hunting for gold, and in quarreling with one another. With the summer came fevers, and soon fifty of the one hundred and five original colonists were dead. Then followed a cold, hard winter, and many of those who had not died of fever in the summer, now died of cold. The colonists brought little food with them, they were too lazy to plant much corn, and they were able to get only small supplies from the Indians. Indeed, the early history of Virginia is given mainly to accounts of "starving times." Of the first thousand colonists not one hundred lived to tell the tale of those early days.

Sir Thomas Dale.

His wise action.

33. Sir Thomas Dale and Good Order.--In 1611 Sir Thomas Dale came out as ruler, and he ruled with an iron hand. If a man refused to work, Dale made a slave of him for three years; if he did not work hard enough, Dale had him soundly whipped. But Sir Thomas Dale was not only a severe man; he was also a wise man. Hitherto everything had been in common. Dale now tried the experiment of giving three acres of land to every one of the old planters, and he also allowed them time to work on their own land.

Tobacco.

Prosperity.

34. Tobacco-growing and Prosperity.--European people were now beginning to use tobacco. Most of it came from the Spanish colonies. Tobacco grew wild in Virginia. But the colonists at first did not know how to dry it and make it fit for smoking. After a few years they found out how to prepare it. They now worked with great eagerness and planted tobacco on every spot of cleared land. Men with money came over from England. They brought many workingmen with them and planted large pieces of ground. Soon tobacco became the money of the colony, and the whole life of Virginia turned on its cultivation. But it was difficult to find enough laborers to do the necessary work.

White servants.

Criminals.

Negro slaves, 1619.

35. Servants and Slaves.--Most of the laborers were white men and women who were bound to service for terms of years. These were called servants. Some of them were poor persons who sold their labor to pay for their passage to Virginia. Others were unfortunate men and women and even children who were stolen from their families and sold to the colonists. Still others were criminals whom King James sent over to the colony because that was the cheapest thing to do with them. In 1619 the first negro slaves were brought to Virginia by a Dutch vessel. The Virginians bought them all--only twenty in number. But the planters preferred white laborers. It was not until more that twenty-five years had passed away that the slaves really became numerous enough to make much difference in the life of the colony.

Sir Edwin Sandys.

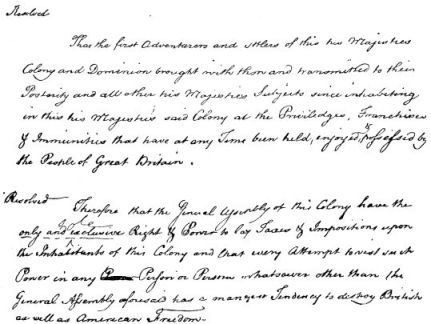

The first American legislature, 1619.

36. The first American Legislature, 1619.--The men who first formed the Virginia Company had long since lost interest in it. Other men had taken their places. These latter were mostly Puritans (p. 29) or were the friends and workers with the Puritans. The best known of them was Sir Edwin Sandys, the playmate of William Brewster--one of the Pilgrim Fathers (p. 29). Sandys and his friends sent Sir George Yeardley to Virginia as governor. They ordered him to summon an assembly to be made up of representatives chosen by the freemen of the colony. These representatives soon did away with Dale's ferocious regulations, and made other and much milder laws.

End of the Virginia Company, 1624.

Virginia a royal province.

37. Virginia becomes a Royal Province, 1624.--The Virginians thought this was a very good way to be governed. But King James thought that the new rulers of the Virginia Company were much too liberal, and he determined to destroy the company. The judges in those days dared not displease the king for he could turn them out of office at any time. So when he told them to destroy the Virginia charter they took the very first opportunity to declare it to be of no force. In this way the Virginia Company came to an end, and Virginia became a royal province with a governor appointed by the king.

Intolerance in Virginia.

Persecution of the Puritans.

38. Religious Intolerance.--In 1625 King James died, and his son Charles became king. He left the Virginians to themselves for the most part. They liked this. But they did not like his giving the northern part of Virginia to a Roman Catholic favorite, Lord Baltimore, with the name of Maryland. Many Roman Catholics soon settled in Lord Baltimore's colony. The Virginians feared lest they might come to Virginia and made severe laws against them. Puritan missionaries also came from New England and began to convert the Virginians to Puritanism. Governor Berkeley and the leading Virginians were Episcopalians. They did not like the Puritans any better than they liked the Roman Catholics. They made harsh laws against them and drove them out of Virginia into Maryland.

Maryland given to Baltimore, 1632.

Settlement of Maryland. Higginson, 121-123;

Eggleston, 50-53; Source-book, 48-51.

39. Settlement of Maryland.--Maryland included the most valuable portion of Virginia north of the Potomac. Beside being the owner of all this land, Lord Baltimore was also the ruler of the colony. He invited people to go over and settle in Maryland and offered to give them large tracts of land on the payment of a small sum every year forever. Each man's payment was small. But all the payments taken together, made quite a large amount which went on growing larger and larger as Maryland was settled. The Baltimores were broad-minded men. They gave their colonists a large share in the government of the colony and did what they could to bring about religious toleration in Maryland.

Roman Catholics in England.

Roman Catholics and Puritans in Maryland.

The Toleration Act, 1649.

40. The Maryland Toleration Act, 1649.--The English Roman Catholics were cruelly oppressed. No priest of that faith was allowed to live in England. And Roman Catholics who were not priests had to pay heavy fines simply because they were Roman Catholics. Lord Baltimore hoped that his fellow Catholics might find a place of shelter in Maryland, and many of the leading colonists were Roman Catholics. But most of the laborers were Protestants. Soon came the Puritans from Virginia. They were kindly received and given land. But it was evident that it would be difficult for Roman Catholics, Episcopalians, and Puritans to live together without some kind of law to go by. So a law was made that any Christian might worship as he saw fit. This was the first toleration act in the history of America. It was the first toleration act in the history of modern times. But the Puritan, Roger Williams, had already established religious freedom in Rhode Island (p. 33).

Tobacco and grain.

Commerce.

Servants and slaves.

41. Maryland Industries.--Tobacco was the most important crop in early Maryland. But grain was raised in many parts of the colony. In time also there grew up a large trading town. This was Baltimore. Its shipowners and merchants became rich and numerous, while there were almost no shipowners or merchants in Virginia. There were also fewer slaves in Maryland than in Virginia. Nearly all the hard labor in the former colony was done by white servants. In most other ways, however, Virginia and Maryland were nearly alike.

The English Puritans.

Non-Conformists.

Separatists.

42. The Puritans.--The New England colonies were founded by English Puritans who left England because they could not do as they wished in the home land. All Puritans were agreed in wishing for a freer government than they had in England under the Stuart kings and in state matters were really the Liberals of their time. In religious matters, however, they were not all of one mind. Some of them wished to make only a few changes in the Church. These were called Non-Conformists. Others wished to make so many changes in religion that they could not stay in the English State Church. These were called Separatists. The settlers of Plymouth were Separatists; the settlers of Boston and neighboring towns were Non-Conformists.

The Scrooby Puritans. Higginson, 55-56;

Eggleston, 34.

They flee to Holland.

They decide to emigrate to America.

43. The Pilgrims.--Of all the groups of Separatists scattered over England none became so famous as those who met at Elder Brewster's house at Scrooby. King James decided to make all Puritans conform to the State Church or to hunt them out of the land. The Scrooby people soon felt the weight of persecution. After suffering great hardships and cruel treatment they fled away to Holland. But there they found it very difficult to make a living. They suffered so terribly that many of their English friends preferred to go to prison in England rather than lead such a life of slavery in Holland. So the Pilgrims determined to found a colony in America. They reasoned that they could not be worse off in America, because that would be impossible. At all events, their children would not grow up as Dutchmen, but would still be Englishmen. They had entire religious freedom in Holland; but they thought they would have the same in America.

BREWSTER'S HOUSE AT SCROOBY.

The Pilgrims held their services in the building on the left,

now used as a cow-house.

The voyage of the Mayflower, 1620.

The Mayflower at Cape Cod.

44. The Voyage across the Atlantic.--Brewster's old friend, Sir Edwin Sandys, was now at the head of the Virginia Company. He easily procured land for the Pilgrims in northern Virginia, near the Dutch settlements (p. 41). Some London merchants lent them money. But they lent it on such harsh conditions that the Pilgrims' early life in America was nearly as hard as their life had been in Holland. They had a dreadful voyage across the Atlantic in the Mayflower. At one time it seemed as if the ship would surely go down. But the Pilgrims helped the sailors to place a heavy piece of wood under one of the deck beams and saved the vessel from going to pieces. On November 19, 1620, they sighted land off the coast of Cape Cod. They tried to sail around the cape to the southward, but storms drove them back, and they anchored in Provincetown harbor.

The Pilgrims Compact, 1620.

45. The Mayflower Compact, 1620.--All the passengers on the Mayflower were not Pilgrims. Some of them were servants sent out by the London merchants to work for them. These men said that as they were outside of Virginia, the leaders of the expedition would have no power over them as soon as they got on land. This was true enough, so the Pilgrims drew up and signed a compact which obliged the signers to obey whatever was decided to be for the public good. It gave the chosen leaders power to make the unruly obey their commands.

The Pilgrims explore the coast. Explorers,

319-328.

Plymouth settled. Higginson,58-60; Eggleston, 35-38;

Source-Book, 39-41.

Sickness and death.

46. The First Winter at Plymouth.--For nearly a month the Pilgrims explored the shores of Cape Cod Bay. Finally, on December 21, 1620, a boat party landed on the mainland inside of Plymouth harbor. They decided to found their colony on the shore at that place. About a week later the Mayflower anchored in Plymouth harbor. For months the Pilgrims lived on the ship while working parties built the necessary huts on shore. It was in the midst of a cold New England winter. The work was hard and food and clothing were not well suited to the worker's needs. Before the Mayflower sailed away in the spring one-half of the little band was dead.

The Pilgrims and the Indians. Explorers,

333-337.

Success of the colony.

New Plymouth colony.

47. New Plymouth Colony.--Of all the Indians who once had lived near Plymouth only one remained. His name was Squanto. He came to the Pilgrims in the spring. He taught them to grow corn and to dig clams, and thus saved them from starvation. The Pilgrims cared for him most kindly as long as he lived. Another and more important Indian also came to Plymouth. He was Massasoit, chief of the strongest Indian tribe near Plymouth. With him the Pilgrims made a treaty which both parties obeyed for more than fifty years. Before long the Pilgrims' life became somewhat easier. They worked hard to raise food for themselves, they fished off the coasts, and bought furs from the Indians. In these ways they got together enough money to pay back the London merchants. Many of their friends joined them. Other towns were settled near by, and Plymouth became the capital of the colony of New Plymouth. But the colony was never very prosperous, and in the end was added to Massachusetts.

Founders of Massachusetts.

Explorers 341-361; Source-book 45-48, 74-76.

Settlement of Massachusetts, 1630. Higginson, 60-64;

Eggleston, 39-41.

48. The Founding of Massachusetts, 1629-30.--Unlike the poor and humble Pilgrims were the founders of Massachusetts. They were men of wealth and social position, as for instance, John Winthrop and Sir Richard Saltonstall. They left comfortable homes in England to found a Puritan state in America. They got a great tract of land extending from the Merrimac to the Charles, and westward across the continent. Hundreds of colonists came over in the years 1629-30. They settled Boston, Salem, and neighboring towns. In the next ten years thousands more joined them. From the beginning Massachusetts was strong and prosperous. Among so many people there were some who did not get on happily with the rulers of the colony.

Roger Williams expelled from Massachusetts.

Higginson, 68-70.

He founds Providence, 1636. Source-book, 52-54.

49. Roger Williams and Religious Liberty.--Among the newcomers was Roger Williams, a Puritan minister. He disagreed with the Massachusetts leaders on several points. For instance, he thought that the Massachusetts people had no right to their lands, and he insisted that the rulers had no power in religious matters--as enforcing the laws as to Sunday. He insisted on these points so strongly that the Massachusetts government expelled him from the colony. In the spring of 1636; with four companions he founded the town of Providence. There he decided that every one should be free to worship God as he or she saw fit.

Mrs. Hutchinson and her friends.

They settle Rhode Island, 1637.

50. The Rhode Island Towns.--Soon another band of exiles came from Massachusetts. These were Mrs. Hutchinson and her followers. Mrs. Hutchinson was a brilliant Puritan woman who had come to Boston from England to enjoy the ministry of John Cotton, one of the Boston ministers. She soon began to find fault with the other ministers of the colony. Naturally, they did not like this. Their friends were more numerous than were Mrs. Hutchinson's friends, and the latter had to leave Massachusetts. They settled on the island of Rhode Island (1637).

The Connecticut colonists.

Founding of Connecticut, 1635-36. Higginson, 71-72.

51. The Connecticut Colony.--Besides those Puritans whom the Massachusetts people drove from their colony there were other settlers who left Massachusetts of their own free will. Among these were the founders of Connecticut. The Massachusetts people would gladly have had them remain, but they were discontented and insisted on going away. They settled the towns of Hartford, Windsor, and Weathersfield, on the Connecticut River. At about the same time John Winthrop, Jr., led a colony to Saybrook, at the mouth of the Connecticut. Up to this time the Dutch had seemed to have the best chance to settle the Connecticut Valley. But the control of that region was now definitely in the hands of the English.

Destruction of the Pequods, 1637.

52. The Pequod War, 1637.--The Pequod Indians were not so ready as the Dutch to admit that resistance was hopeless. They attacked Wethersfield. They killed several colonists, and carried others away into captivity. Captain John Mason of Connecticut and Captain John Underhill of Massachusetts went against them with about one hundred men. They surprised the Indians in their fort. They set fire to the fort, and shot down the Indians as they strove to escape from their burning wigwams. In a short time the Pequod tribe was destroyed.

[Illustration: JOHN WINTHROP, JR.]

The Connecticut Orders of 1638-39.

53. The First American Constitution, 1638-39.--The Connecticut colonists had leisure now to settle the form of their government. Massachusetts had such a liberal charter that nothing more seemed to be necessary in that colony. The Mayflower Compact did well enough for the Pilgrims. The Connecticut people had no charter, and they wanted something more definite than a vague compact. So in the winter of 1638-39 they met at Hartford and set down on paper a complete set of rules for their guidance. This was the first time in the history of the English race that any people had tried to do this. The Connecticut constitution of 1638-39 is therefore looked upon as "the first truly political written constitution in history." The government thus established was very much the same as that of Massachusetts with the exception that in Connecticut there was no religious condition for the right to vote as there was in Massachusetts.

The New Haven settlers.

New Haven founded, 1638. Higginson, 72-73.

54. New Haven, 1638.--The settlers of New Haven went even farther than the Massachusetts rulers and held that the State should really be a part of the Church. Massachusetts was not entirely to their tastes. They passed only one winter there and then moved away and settled New Haven. But this colony was not well situated for commerce, and was too near the Dutch settlements (p. 41). It was never as prosperous as Connecticut and was finally joined to that colony.

Reasons for union.

Articles of Confederation, 1643.

New England towns. Higginson, 47-79.

55. The New England Confederation, 1643.--Besides the settlements that have already been described there were colonists living in New Hampshire and in Maine. Massachusetts included the New Hampshire towns within her government, for some of those towns were within her limits. In 1640 the Long Parliament met in England, and in 1645 Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans destroyed the royal army in the battle of Naseby. In these troubled times England could do little to protect the New England colonists, and could do nothing to punish them for acting independently. The New England colonists were surrounded by foreigners. There were the French on the north and the east, and the Dutch on the west. The Indians, too, were living in their midst and might at any time turn on the whites and kill them. Thinking all these things over, the four leading colonies decided to join together for protection. They formed the New England Confederation, and drew up a constitution. The colonists living in Rhode Island and in Maine did not belong to the Confederation, but they enjoyed many of the benefits flowing from it; for it was quite certain that the Indians and the French and the Dutch would think twice before attacking any of the New England settlements.

[Illustration: A CHILD'S HIGH CHAIR, ABOUT 1650.]

Education.

56. Social Conditions.--The New England colonies were all settled on the town system, for there were no industries which demanded large plantations--as tobacco-planting. The New Englanders were small farmers, mechanics, ship-builders, and fishermen. There were few servants in New England and almost no negro slaves. Most of the laborers were free men and worked for wages as laborers now do. Above all, the New Englanders were very zealous in the matter of education. Harvard College was founded in 1636. A few years later a law was passed compelling every town to provide schools for all the children in the town.

The Dutch East India Company.

57. The Dutch.--At this time the Dutch were the greatest traders and shipowners in the world. They were especially interested in the commerce of the East Indies. Indeed, the Dutch India Company was the most successful trading company in existence. The way to the East Indies lay through seas carefully guarded by the Portuguese, so the Dutch India Company hired Henry Hudson, an English sailor, to search for a new route to India.

Henry Hudson.

He discovers Hudson's River, 1609. Higginson, 88-90;

Explorers, 281-296.

His death. Explorers 296-302.

58. Hudson's Voyage, 1609.--He set forth in 1609 in the Half-Moon, a stanch little ship. At first he sailed northward, but ice soon blocked his way. He then sailed southwestward to find a strait, which was said to lead through America, north of Chesapeake Bay. On August 3, 1609, he reached the entrance of what is now New York harbor. Soon the Half-Moon entered the mouth of the river that still bears her captain's name. Up, up the river she sailed, until finally she came to anchor near the present site of Albany. The ship's boats sailed even farther north. Everywhere the country was delightful. The Iroquois came off to the ship in their canoes. Hudson received them most kindly--quite unlike the way Champlain treated other Iroquois Indians at about the same time, on the shore of Lake Champlain (p. 20). Then Hudson sailed down the river again and back to Europe. He made one later voyage to America, this time under the English flag. He was turned adrift by his men in Hudson's Bay, and perished in the cold and ice.

The Dutch fur-traders.

Settle on Manhattan Island.

New Netherland.

59. The Dutch Fur-Traders.--Hudson's failure to find a new way to India made the Dutch India Company lose interest in American exploration. But many Dutch merchants were greatly interested in Hudson's account of the "Great River of the Mountain." They thought that they could make money from trading for furs with the Indians. They sent many expeditions to Hudson's River, and made a great deal of money. Some of their captains explored the coast northward and southward as far as Boston harbor and Delaware Bay. Their principal trading-posts were on Manhattan Island, and near the site of Albany. In 1614 some of the leading traders obtained from the Dutch government the sole right to trade between New France and Virginia. They called this region New Netherland.

The Dutch West India Company, 1621.

Higginson, 90-96; Explorers, 303-307;

Source-book, 42-44.

The patroons, 1628.

60. The Founding of New Netherland.--In 1621 the Dutch West India Company was founded. Its first object was trade, but it also was directed "to advance the peopling" of the American lands claimed by the Dutch. Colonists now came over; they settled at New Amsterdam, on the southern end of Manhattan Island, and also on the western end of Long Island. By 1628 there were four hundred colonists in New Netherland. But the colony did not grow rapidly, so the Company tried to interest rich men in the scheme of colonization, by giving them large tracts of land and large powers of government. These great land owners were called patroons. Most of them were not very successful. Indeed, the whole plan was given up before long, and land was given to any one who would come out and settle.

Governor Kieft.

Kieft orders the Indians to be killed.

Results of the massacre.

61. Kieft and the Indians, 1643-44.--The worst of the early Dutch governors was William Kieft (Keeft). He was a bankrupt and a thief, who was sent to New Netherland in the hope that he would reform. At first he did well and put a stop to the smuggling and cheating which were common in the colony. Emigrants came over in large numbers, and everything seemed to be going on well when Kieft's brutality brought on an Indian war that nearly destroyed the colony. The Indians living near New Amsterdam sought shelter from the Iroquois on the mainland opposite Manhattan Island. Kieft thought it would be a grand thing to kill all these Indian neighbors while they were collected together. He sent a party of soldiers across the river and killed many of them. The result was a fierce war with all the neighboring tribes. The Dutch colonists were driven from their farms. Even New Amsterdam with its stockade was not safe. For the Indians sometimes came within the stockade and killed the people in the town. When there were less than two hundred people left in New Amsterdam, Kieft was recalled, and Peter Stuyvesant was sent as governor in his stead.

Peter Stuyvesant. Higginson, 97.

62. Stuyvesant's Rule.--Stuyvesant was a hot-tempered, energetic soldier who had lost a leg in the Company's service. He ruled New Netherland for a long time, from 1647 to 1664. And he ruled so sternly that the colonists were glad when the English came and conquered them. This unpopularity was not entirely Stuyvesant's fault. The Dutch West India Company was a failure. It had no money to spend for the defence of the colonists, and Stuyvesant was obliged to lay heavy taxes on the people.

The Swedes on the Delaware. Higginson,

106-108.

Stuyvesant conquers them.

63. New Sweden.--When the French, the English, and the Dutch were founding colonies in America, the Swedes also thought that they might as well have a colony there too. They had no claim to any land in America. But Swedish armies were fighting the Dutchmen's battles in Europe. So the Swedes sent out a colony to settle on lands claimed by the Dutch. As long as the European war went on, the Swedes were not interfered with. But when the European war came to an end, Stuyvesant was told to conquer them. This he did without much trouble, as he had about as many soldiers as there were Swedish colonists. In this way New Sweden became a part of New Netherland.

Summary.

The Chesapeake Colonies.

The New England Colonies.

64. Summary.--We have seen how the French, the Dutch, the Swedish, and the English colonies were established on the Atlantic seashore and in the St. Lawrence valley. South of these settlements there was the earlier Spanish colony at St. Augustine. The Spanish colonists were very few in number, but they gave Spain a claim to Florida. The Swedish colony had been absorbed by the stronger Dutch colony. We have also seen how very unlike were the two English groups of colonies. They were both settled by Englishmen, but there the likeness stops. For Virginia and Maryland were slave colonies. They produced large crops of tobacco. The New England colonists on the other hand were practically all free. They lived in towns and engaged in all kinds of industries. In the next hundred years we shall see how the English conquered first the Dutch and then the French; how they planted colonies far to the south of Virginia and in these ways occupied the whole coast north of Florida.

CHAPTER 4

§§ 26, 27.--a. Mark on a map all the places mentioned in these sections.

b. Describe Champlain's attacks on the Iroquois.

§§ 28-30.--a. Compare the reasons for the coming of the French and the Spaniards.

b. What work did the Jesuits do for the Indians?

c. Explain carefully why the hostility of the Iroquois to the French was so important.

CHAPTER 5

§§ 31, 32.--a. Give two reasons for the revival of English colonial enterprises.

b. Describe the voyage and early experiences of the Virginia colonists.

c. Give three reasons for the sufferings of the Virginia colonists.

§§ 33-35.--a. What do you think of Sir Thomas Dale?

b. To what was the prosperity of Virginia due? Why?

c. What classes of people were there in Virginia?

§§ 36-38.--a. What is the meaning of the word "Puritan" (see § 43)? Why is Sir Edwin Sandys regarded as the founder of free government in the English colonies?

b. Describe the laws of Virginia as to Roman Catholics and Puritans.

§§ 39-41.--a. Describe Lord Baltimore's treatment of his settlers. What do you think of the wisdom of his actions?

b. How were Roman Catholics treated in England?

c. What is meant by toleration? Who would be excluded by the Maryland Toleration Act?

d. Describe the likenesses and the differences between Virginia and Maryland.

CHAPTER 6

§§ 42-47.--a. Describe the voyage of the Mayflower.

b. What was the object of the Mayflower Compact?

c. Describe the Pilgrims' search for a place of settlement.

d. Read Bradford's account of the first winter at Plymouth.

e. What did Squanto do for the Pilgrims?

§§ 48-50.--a. What advantages did the founders of Massachusetts have over those of New Plymouth?

b. Look up the history of England, 1630-40, and say why so many colonists came to New England in those years.

c. On what matters did Roger Williams disagree with the rulers of Massachusetts?

d. How are Williams's ideas as to religious freedom regarded now?

e. Why was Mrs. Hutchinson expelled from Massachusetts?

§§ 51-54.--a. How did the Pequod War affect the colonists on the Connecticut?

b. What is a constitution? Why did the Connecticut people feel the need of one? Why is the Connecticut constitution famous?

c. Why did the New Haven settlers found a separate colony?

§§ 55, 56.--a. What two parties were fighting in England?

b. Give all the reasons for the formation of the New England Confederation. What were the effects of this union?

c. Compare the industries of New England with those of Virginia.

CHAPTER 7

§§ 57-59.--a. Why did the Dutch East India Company wish a northern route to India?

b. Describe Hudson's and Champlain's expeditions, and compare their treatment of the Iroquois.

c. What attracted the Dutch to the region discovered by Hudson?

§§ 60-62.--a. What was the object of the Dutch West India Company? What privileges did the patroons have?

b. Describe the career of Kieft. What were the results of his treatment of the Indians?

c. What kind of a governor was Stuyvesant? Why was he unpopular?

§ 63.--a. In what European war were the Swedes and the Dutch engaged?

b. On what land did the Swedes settle?

c. Describe how New Sweden was joined to New Netherland.

GENERAL QUESTIONS

a. Mark on a map in colors the lands settled by the different European nations.

b. Note the position of the Dutch with reference to the English, and explain the importance of such position.

c. Give one fact about each of the colonies, and state why you think it important.

d. Give one fact which especially interests you in connection with each colony, and explain your interest.

e. In which colony would you have liked to live, and why?

TOPICS FOR SPECIAL WORK

a. Champlain's place in American history (Parkman's Pioneers).

b. The First American Legislature and its work (Hart's Contemporaries, I., No. 65).

c. Why did the Pilgrims come to America? (Bradford's Plymouth).

d. Arrange a table of the several settlements similar to that described on page 18.

e. Write a composition on life in early colonial days (Eggleston's United States, 91-113).

SUGGESTIONS TO THE TEACHER

In treating this chapter aim to make clear the reasons for and conditions of the settlement of each colony. Vividness can best be obtained by a study of the writings of the time, especially of Bradford's History of Plymouth. Use pictures in every possible way and molding board as well.

Emphasize the lack of true liberty of thought, and lead the children to understand that persecution was a characteristic of the time and not a failing of any particular colony or set of colonists.

References.--Fiske's United States for Schools 133-180; McMaster's School History, 93-108 (life in 1763); Source-Book, ch. vii; Fisher's Colonial Era; Earle's Child Life.

Home Readings.--Parkman's Montcalm and Wolfe; Franklin's Autobiography; Brooks's In Leisler's Times; Coffin's Old Times in the Colonies; Cooper's Last of the Mohicans; Scudder's Men and Manners One Hundred Years Ago.

The Puritan in England. Higginson and Channing,

English History for Americans, 182-195.

The Colonies, 1649-60.

65. The Puritans and the Colonists, 1649-60.--In 1649 Charles I was executed, and for eleven years the Puritans were supreme in England. During this time the New England colonists governed themselves, and paid little heed to the wishes and orders of England's rulers. After some hesitation, the Virginians accepted the authority of Cromwell and the Puritans. In return they were allowed to govern themselves. In Maryland the Puritans overturned Baltimore's governor and ruled the province for some years.

The Restoration, 1660. English History for

Americans, 196.

The Navigation Laws.

66. Colonial Policy of Charles II.--In 1660 Charles II became king of England or was "restored" to the throne, as people said at the time. Almost at once there was a great revival of interest in colonization, and the new government interfered vigorously in colonial affairs. In 1651 the Puritans had begun the system of giving the English trade only to English merchants and shipowners. This system was now extended, and the more important colonial products could be carried only to English ports.

Charles II and Massachusetts.

Massachusetts and the Quakers. Higginson, 80-81.

67. Attacks on Massachusetts.--The new government was especially displeased by the independent spirit shown by Massachusetts. Only good Puritans could vote in that colony, and members of the Church of England could not even worship as they wished. The Massachusetts people paid no heed whatever to the navigation laws and asserted that acts of Parliament had no force in the colony. It chanced that at this time Massachusetts had placed herself clearly in the wrong by hanging four persons for no other reason than that they were Quakers. The English government thought that now the time had come to assert its power. It ordered the Massachusetts rulers to send other Quakers to England for trial. But, when this order reached Massachusetts, there were no Quakers in prison awaiting trial, and none were ever sent to England.

Charters of Connecticut and Rhode Island,

1662-63.

New Haven absorbed by Connecticut.

68. Connecticut and Rhode Island.--While the English government was attacking Massachusetts it was giving most liberal charters to Connecticut and to Rhode Island. Indeed, these charters were so liberal that they remained the constitutions of the states of Connecticut and Rhode Island until long after the American Revolution. The Connecticut charter included New Haven within the limits of the larger colony and thus put an end to the separate existence of New Haven.

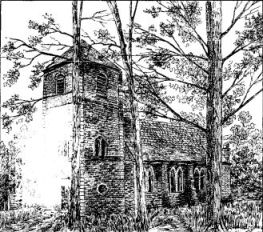

THE OLDEST CHURCH SOUTH OF THE POTOMAC.

The English conquest of New Netherland, 1664. Higginson. 97-98.

69. Conquest of New Netherland, 1664.--The English government now determined to conquer New Netherland. An English fleet sailed to New Amsterdam. Stuyvesant thumped up and down on his wooden leg. But he was almost the only man in New Amsterdam who wanted to fight. He soon surrendered, and New Netherland became an English colony. The Dutch later recaptured it and held it for a time; but in 1674 they finally handed it over to England.

New Netherland given to the Duke of York and Albany.

70. New York.--Even before the colony was seized in 1664, Charles II gave it away to his brother James, Duke of York and Albany, who afterward became king as James II. The name of New Netherland was therefore changed to New York, and the principal towns were also named in his honor, New York and Albany. Little else was changed in the colony. The Dutch were allowed to live very nearly as they had lived before, and soon became even happier and more contented than they had been under Dutch rule. Many English settlers now came in. The colony became rich and prosperous, but the people had little to do with their own government.

Origin of New Jersey, 1664.

Settlement of New Jersey.

71. New Jersey.--No sooner had James received New Netherland from his brother than he hastened to give some of the best portions of it to two faithful friends, Sir George Carteret and Lord Berkeley. Their territory extended from New York harbor to the Delaware River, and was named New Jersey in honor of Carteret's defense of the island of Jersey against the Puritans. Colonists at once began coming to the new province and settled at Elizabethtown.

East and West Jersey.

Prosperity.

72. Later New Jersey.--Soon New Jersey was divided into two parts, East Jersey and West Jersey. West Jersey belonged to Lord Berkeley and he sold it to the Quakers. Not very many years later the Quakers also bought East Jersey. The New Jersey colonists were always getting into disputes with one another, so they asked Queen Anne to take charge of the government of the province. This she did by telling the governor of New York to govern New Jersey also. This was not what the Jersey people had expected. But they had their own legislature. In time also they secured a governor all to themselves and became a royal province entirely separate from New York. Pennsylvania and New York protected the Jersey people from the French and the Indians, and provided markets for the products of the Jersey farms. The colonists were industrious and their soil was fertile. They were very religious and paid great attention to education. New Jersey became very prosperous and so continued until the Revolution.

Founding of Carolina, 1663. Higginson, 124-127.

73. The Founding of Carolina.--The planting of New Jersey was not the only colonial venture of Carteret and Berkeley. With Lord Chancellor Clarendon and other noblemen they obtained from Charles land in southern Virginia extending southward into Spanish Florida. This great territory was named Carolina.

Northern Carolina.

Southern Carolina.

74. The Carolina Colonists.--In 1663, when the Carolina charter was granted, there were a few settlers living in the northern part of the colony. Other colonists came from outside mainly from the Barbadoes and settled on the Cape Fear River. In this way was formed a colony in northern Carolina. But the most important settlement was in the southern part of the province at Charleston. Southern Carolina at once became prosperous. This was due to the fact that the soil and climate of that region were well suited to the cultivation of rice. The rice swamps brought riches to the planters, they also compelled the employment of large numbers of negro slaves. Before long, indeed, there were more negroes than whites in southern Carolina. In this way there grew up two distinct centers of colonial life in the province.

[Illustration: Southern Carolina.]

Indian war.

Bacon's Rebellion, 1676.

75. Bacon's Rebellion, 1676.--By this time the Virginians had become very discontented. There had been no election to the colonial assembly since 1660 and Governor Berkeley was very tyrannical. The Virginians also wanted more churches and more schools. To add to these causes of discontent the Indians now attacked the settlers, and Berkeley seemed to take very little interest in protecting the Virginians. Led by Nathaniel Bacon the colonists marched to Jamestown and demanded authority to go against the Indians. Berkeley gave Bacon a commission. But, as soon as Bacon left Jamestown on his expedition, Berkeley declared that he was a rebel. Bacon returned, and Berkeley fled. Bacon marched against the Indians again, and Berkeley came back, and so the rebellion went on until Bacon died. Berkeley then captured the other leaders one after another and hanged them. But when he returned to England, Charles II turned his back to him, saying, "The old fool has killed more men in Virginia than I for the murder of my father."

[Illustration: THE HOUSE IN WHICH NATHANIEL BACON DIED. From an original sketch.]

Greedy Governors.

Founding of William and Mary College, 1691.

76. Virginia after Bacon's Rebellion.--The Virginians were now handed over to a set of greedy governors. Some of them came to America to make their fortunes. But some of them were governors whom the people of other colonies would not have. The only event of importance in the history of the colony during the next twenty-five years was the founding of William and Mary College (1691) at Williamsburg. It was the second oldest college in the English colonies.

[Illustration: THE OPENING LINES OF THE PENNSYLVANIA CHARTER SHOWING ORNAMENTAL BORDER AND PORTRAIT OF CHARLES II.]

King Philip's War, 1675-76. Higginson, 137-138; Eggleston, 81-89.

77. King Philip's War, 1675-76.--It was not only in Virginia and Maryland that the Indians were restless at this time. In New England also they attacked the whites. They were led by Massasoit's son, King Philip, an able and far-seeing man. He saw with dismay how rapidly the whites were driving the Indians away from their hunting-grounds. The Indians burned the English villages on the frontier and killed hundreds of the settlers. The strongest chief to join Philip was Canonchet of the Narragansetts. The colonial soldiers stormed his fort and killed a thousand Indian warriors. Before long King Philip himself was killed, and the war slowly came to an end.

William Penn.

The Pennsylvania Charter, 1681.

78. William Penn.--Among the greatest Englishmen of that time was William Penn. He was a Quaker and was also a friend of Charles II and James, Duke of York. He wished to found a colony in which he and the Quakers could work out their ideas in religious and civil matters. It chanced that Charles owed Penn a large sum of money. As Charles seldom had any money, he was very glad to give Penn instead a large tract of land in America. In this way Penn obtained Pennsylvania. James, for his part, gave him Delaware.

Settlement of Pennsylvania, 1682. Higginson, 101-105; Eggleston, 57-60; Source-Book, 67-69.